The Cycle of Discontent

Oct 2018 by Neil McKinnon

How a parochial focus on TTM can lead a business into a cycle of discontent.

Reaction can be one of the most challenging aspects of managing change in a business. Why? Too much reaction can restrict business growth and innovation.

Constant Reaction leads to what I term the Cycle of Discontent. Paradoxically, it can be caused by a business’ desire to meet TTM and ROI desires. See the figure below.

The Cycle of Discontent

The cycle has four phases:

- Constant Reaction.

- Constraining Force.

- Debt Accrual.

- Slower & Slower Deliveries.

Let's look at each in more depth.

Phase 1 — Constant Reaction

The cycle begins when constant reaction becomes the norm. It often stems from external influences (e.g. a customer wants a product or service that you can, or will be able to offer, but needs it yesterday).

Typically these external influences offer (seemingly) sufficient incentive to undertake a project, so the two parties agree, formalize it (with a contract), and work begins. The project either goes to plan (on time and budget, and of satisfactory quality), or it doesn’t.

Note — What is Reaction?

Reaction looks to the past. Sometimes it’s dim-and-distant, sometimes it’s very recent, but… it’s still the past. Thus, Reaction indicates that you’re not looking at what’s to come; you’re probably not innovating; and you’re probably not looking to the next disruptive innovation that could shake up your industry...

Onto the second phase — Constraining Force.

Phase 2 — Constraining Force

Constraining Force can occur anywhere in a project lifecycle. It is the inability to think, assign sufficient resource, or time, to satisfy the desired outcomes/properties of all stakeholders.

When reaction is constant, there is rarely sufficient time, or resource, to fully analyse, understand, and contextualise the problem, and thus, to identify the correct solution, based upon the common deciding factors of costs, time, and quality.

Note — Causes of Constraining Force

Constraining Force is often caused by assumptions made earlier on in the process that are later discovered to be incorrect.

Let's say the project (described in the previous section) doesn’t go to plan — maybe insufficient time was allowed to undertake a technical due diligence, and a key concept is unworkable in the manner assumed (assumed is the key word here) when the contract was drawn up; what options are open to us?

We can:

- Renege on the deal, incur any costs associated with our contractual obligations, and (potentially) suffer reputational damage to our brand, or

- Ask for more time and/or money; this is possible but unlikely, and also has brand reputational implications, or

- Undertake the work, but soak up the costs internally, and (hopefully) learn our lesson, or

- (unfortunately) View quality as a mutable (and subjective) quality.

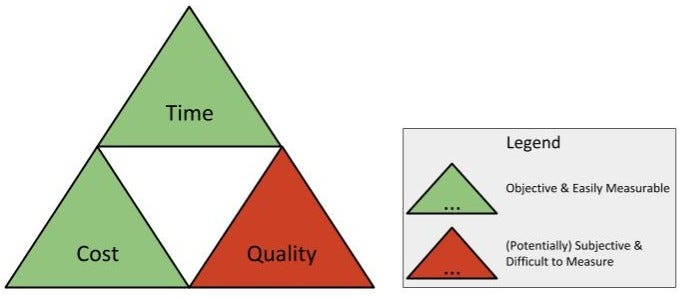

Figure 2 shows an example of the Iron Triangle.

Figure 2 — The Iron Triangle

The Iron Triangle is uncompromising; you can only satisfy two of the three qualities (remember that NASA poster?). Also, note that I’ve extended the concept to indicate the objectivity (or ease of measurability) of each attribute (green is objective, red is subjective). Whilst Time and Cost are generally objective, empirical, and (reasonably) easy to measure (“oops, that’ll push us over budget!”), Quality may not be.

One person’s view of quality may differ radically from another's. And even if there’s a consensus, quality covers such a broad and diverse range of areas and subjects, that it is difficult to measure in the entirety (anyone who’s attempted to build a suite of tests to prove a system’s performance/load can subscribe to that). What we’re potentially trying to measure is Perspective.

Note — Reaching a Quality Consensus

Due to the involvement of two parties, reaching a consensus can be extremely challenging. Often, things are left unsaid, remain subjective and thus unmeasurable, and return to cause future problems (clarity is essential).

There’s another consideration too; a customer may not understand quality within the domain (e.g. software). Often, a customer specializes in a particular business domain (e.g. retail, banking), not in software construction, or what constitutes for quality in this realm. This, by the way, can also be true of third-party vendors offering other solution aggregators with part of that software solution.

To offer up another analogy, some time ago I bought a new door (and surroundings) for my house. We chose a high quality (and reasonably expensive) door from the showroom, which also included fitting. When it was fitted, the door was fine, but the surroundings (I felt) were sloppily fitted and done in haste. Although I didn’t complain (I didn’t feel I had sufficient domain knowledge to do so), my concerns were later founded when a strong wind blew a cold draft of air through one of the poor fittings. The moral of the story? The fitter’s perspective of quality differed from mine, and even though I was no expert, I knew enough to understand quality in a domain I had no real expertise in (and that I should have believed in myself more).

Now... that company got their money, but… they will never get another penny from me. Their short-sighted treatment of quality as a second-class citizen has undermined their brand reputation in my eyes, and is unsalvageable.

Note — Even Software Vendors Can Get Quality Wrong

I’ve worked with several vendors (including one industry heavyweight) who supplied a front-end solution that was, at least by my standards, well below quality expectations. I’ve also been on the receiving end, when we were forced (against my better judgement) to deliver a solution we knew to be below par, but had no influence to change; very demoralizing.

Note — Trust Isn’t a Good Measurement for Quality

Because quality can be notoriously difficult to agree and measure, some parties base their quality decisions on trust; e.g. customer A trusts vendor B to deliver a robust solution. This, to me, can place the customer (and possibly the vendor) in a precarious position (it’s enticing the vendor to behave in a manner that may not suit either party over the longer term; that vendor may also become complacent around quality, and be in store for a rude awakening when the customer finally realizes where the problem lies).

Onto phase 3 — Debt Accrual.

Phase 3 — Debt Accrual

If Constraining Force has impacted quality (i.e. corners are cut to deliver the feature), then over time, Technical Debt accrues. This Debt Accrual starts small, but quickly mounts up as the cycle repeats, with no remedial action.

Being (potentially) subjective, it may seem like some of the decisions that affect quality are unimportant. For instance, removing layers from a system to deliver a UI more quickly, by directly interacting with a database, may seem relatively innocuous, but it can have more insidious long-term ramifications (it tightly couples UI to database, and hampers evolvability, scalability, and reuse, to name a few).

These debts are poor decisions, done for both right and wrong reasons, that are never resolved (“paid back” in debt parlance). They cause us to employ a “band-aid development methodology”, where unnecessary, and overly-complex work become the norm, often without people realizing its cause.

Note — Technical Debt & Business Execs

My past experiences of the attitude of many business executives towards technical debt has not been positive. Some execs hadn’t heard of it, or didn’t understand it; however, the ones who concerned me most treated technical debt as a chimera, invented by technologists to excuse poor quality, or the inability to meet TTM expectations.

I wholeheartedly disagree. I’ve seen this cycle at play, including the technical debts caused by business reaction, and they had very serious ramifications.

This leads to phase 4 — Slower Deliveries.

Phase 4 — Slower & Slower Deliveries

Debt Accrual leads to the final stage; Slower Deliveries. Each change has greater risk, is more complex, and/or touches many unnecessary areas (i.e. “band-aid development methodology”). Thus, tasks become harder, and take longer. In the most severe cases, the level of debt causes Change Friction and prevents any change.

Slower Deliveries have some important business ramifications:

- Poor Time-To-Market (TTM) — feedback is slow, opportunities are missed, and unnecessary effort is spent on failing features with little value.

- Poor long-term Return-On-Investment (ROI) — unnecessary effort is spent on failing features, and productivity is poor.

- Reduced Brand Reputation — it becomes increasingly difficult to satisfy client demands and brand reputation is (potentially fatally) affected.

Summary

Through Constant Reaction, all of the things that we aspired to (TTM and ROI) have actually slowed us, and caused the TTM and ROI issues we now face. How about that for a paradox?

Watch this one. I’ve seen this cycle in practice, where TTM and Costs are given sustained precedence over quality. Quality is the easiest one to sacrifice, often because it’s the easiest to encapsulate from others. People who focus too heavily on TTM and cost-effectiveness, paying lip-service to quality, actually slow everyone down, and inflate the costs of every future change.

That's not to say that you shouldn’t sometimes trade off quality to meet TTM (it might be the difference between a sale, or no sale). But always be aware of the ramifications of these decisions, and be willing to pay-off debts regularly, before they become a major obstacle.

Reaction is a good way to emphasize your commitment to clients. Yet, there’s such a concept as too much of a good thing. Without some push-back, clients can dictate your quality, and diminish their own business. You get stuck in the cycle, and can find escape difficult.