Appendix A

CONTROL

Throughout my career I’ve encountered multiple executives who were willing to forgo Control of a feature or product to another party, often without undertaking sufficient Due Diligence, or considering the ramifications or practicalities (Feasibility v Practicality) involved in such a decision.

The results were mixed. Sometimes sacrificing boosted capacity at a key stage in delivery, or improved ROI (why use key resources on Table Stakes features that don’t excite customers?), leading to early delivery and a positive customer experience. However, I’ve witnessed just as many poor outcomes, leading to missed deliveries, unhappy (internal and external) customers, poor quality (affecting long-term Sustainability), and reputational harm.

In this section I discuss some forms of Control, and offer some advice on what I term Common Sense Control; i.e. how much Control you should expect over a product, feature, or technological solution.

WHAT IS CONTROL?

Firstly, what is Control?

Google’s dictionary defines Control as:

“the power to influence or direct people's behaviour or the course of events,” or to “maintain influence or authority over.”

I’ve bolded the key words.

Both descriptions highlight the keyword influence. One talks of authority (i.e. a form of power, that influences behaviour), the other directly references the word behaviour. The final key words are course of events; i.e. we influence something or someone to adapt their path (course) to be (generally) more favourable to oneself.

Allow me then to paraphrase this in the context of a software product. Control provides a way to shape or influence the direction that a product, feature, distribution, or culture takes, to be favourable to oneself.

CONTROL GRANULARITY

I’ve worked with customers who’ve dictated priorities (i.e. what is worked on first), aspects of how it’s built, when it’s delivered (e.g. only when they’re ready for it), and even the manner of delivery (e.g. fortnightly, continuously). This Fine-Grained Control tends to be rather intrusive, and allows one party to influence both broadly and deeply (i.e. into the minutiae).

The converse - Coarse-Grained Control - has more of a directional influence, such as what goes into a product roadmap and its delivery sequence, or a general feature-set for a new domain, is less intrusive, and - in the right circumstances - can be powerful.

CONTROL & DEPENDENCIES

Control and dependencies are linked. Interdependencies (whether it’s a person, product, or technology) typically increase the import of external control, whilst the converse is generally true of the self-sufficient.

Supplier change cycles are another important consideration. TTM is paramount to many suppliers, who simply cannot afford to be held up by tardy consumers, else they lose their competitive advantage (Flow).

So, unless they’ve a (very) good reason, that supplier probably won’t slow for you (and may not even know of you). From the suppliers perspective, their Definition of Done is when the service/product is available to their customer; not necessarily used by them, or by that customer’s customers. The morale of the story? You can’t control their velocity, but you can control your own.

WHY IS CONTROL IMPORTANT?

As I described earlier, Control provides the ability to influence the direction a product or feature(s) takes, and therefore, its lifetime (ROI).

LIMITED CONTROL, LIMITED INFLUENCE

Limited Control indicates little (if any) negotiating power, and little control over change (the biggest influencer in any industry?) outwith their own zone of influence. Conversely, expansive Control typically involves making many more decisions.

Consider - for instance - the case where you’re building a software product upon a platform from a well-respected vendor, of which you have little Control of what changes, and when (Change Impotence). The vendor already supports many customers; however, to remain competitive must continue to provide value, and maintain a good rhythm of change. They do this by regularly releasing new features (in the form of minor and major versions) to the market.

Meanwhile, in parallel, we find you - a consumer of that vendor service - focused on delivering your own form of value to your customers; again, in the form of regular feature releases. The velocity difference might be (at an entirely arbitrary level):

| Month | Vendor (per month) | You (per month) | Velocity Difference (Delta) | Queued Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 2018 | 20 | 3 | 17 | 20 |

| Aug 2018 | 23 | 5 | 35 (18 + 17) | 43 |

| Sep 2018 | 18 | 4 | 49 (35 + 14) | 61 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| July 2020 | 29 | 7 | 200+ | 500+ |

As you can see, the vendor continues to release new features in parallel to you releasing your own; however, notice the disparity in the number of features you deliver, versus what the supplier can produce (logic dictates that for every feature you release, the vendor releases many more). Additionally, whilst those supplier features may need incorporated into your product, they are far less likely to be actioned (they’re often given a second-class status against functionality your business offers), and (probably) wait in a queue (a form of invisible Inventory) in front of your business.

Note that both desirable and undesirable (or uninteresting) improvements, and even any critical security patches, remain in that inventory queue, potentially for a lengthy period (I used two years in this example). And whilst many of these changes may be irrelevant, some will (or will become) deeply important to you. As such, we’re no longer describing “nice-to-have” product improvements, but the fundamental needs required to build a sustainable product.

Fear not, we’ll incorporate the vendor changes (upgrade) when we have available capacity. Yet danger lies below the surface. It is easy to become blinkered to only solving your own immediate problems (i.e. building your own product, in the form of Functional Myopicism).

Let’s say those two years have now passed, the business frees up some capacity, and the upgrade task begins. We can approximate the scale of the task by the size of the inventory queue in front of the business. In our case, we soon realise it’s too vast to resolve.

Maybe we could cherry-pick? It would make good sense, since we don’t need most of the changes - “just those 20%, for critical security patches and a few features to increase our productivity.” Unfortunately, it’s probably too late, and mainly relates to the two forms of dependencies you must manage:

- The dependencies between the system you’ve built, and the vendor features they rely upon.

- The interrelated dependencies between the vendor features, all within the vendor’s domain.

The first dependency relates to your dependence upon features that the vendor may have changed (improved, or removed), which may initiate a reciprocating change within your system. The second form is less obvious.

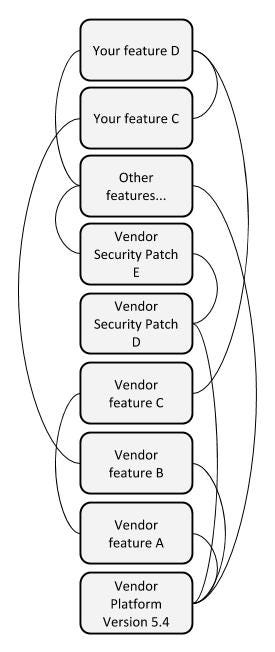

Most features don’t live in isolation. As they say in scientific circles, they “stand upon the shoulders of giants” - e.g. the evolution of human knowledge is heavily influenced by the many cognitive leaps made by our forebears, which we build upon. In software parlance, we find that each built feature relies upon many other features, and we make Availability Assumptions about their existence. At a very rudimentary level, we might describe these dependencies like so:

Dependecy Tree Example

Typically, a real dependency tree is far more complex than this, but it serves its purpose.

Let’s say you need “Vendor Security Patch E” (which sits around the middle of all the released features, so may depend upon any, or all, of them). Whilst you may not need any features above it, you probably - due to coupling - need everything below it. And influenced by the granularity of the vendor’s release packaging strategy, it may require you to pick up everything above it anyway.

Cherry-picking quickly becomes impractical when faced with this problem; there’s practically no way to extricate a single feature from all its other dependencies (and subsequently the features that they rely upon).

The outcome? We find ourselves crippled by change. We have lost Control of the external change cycle used to feed improvements into your product, affecting our ability to improve our product, its agility, modernity, security, stability, and thus, its value. Innovation is also affected, as we now face issues:

- Sourcing and hiring staff to maintain (what is rapidly becoming) an antiquated system.

- Motivating and retaining existing staff, who crave modernity, and efficient technologies/practices.

A second-level outcome of this is that we begin to circumvent good practice (we work around the system rather than with it) to keep it alive, rather than evolving it, whilst a shadow of realisation slowly dawns on us that our patient has an incurable disease (Entropy controls you). System (not business) constraints challenge all innovation; change becomes a matter of identifying circumventions to highly-contextual problems (which few others have encountered, so expect little support). A third-level outcome being the pollution of our culture with this stilted mindset, slowing the entire production line, and causing TTM, ROI, Agility, Sellability, and Brand Reputational harm.

EVOLUTION & CODEMODS

Facebook - the originator of the React.js JavaScript framework - introduced the concept of the “codemod” to try and counter the problem of better control of change management.

“codemod is a tool/library to assist you with large-scale codebase refactors that can be partially automated but still require human oversight and occasional intervention.” [1]

Being a heavy consumer of their own framework, they wished to reap the innovation benefits from a fast-evolving framework, against the backdrop of a supporting Safety Net, protecting them from costly, or unproductive changes; i.e. balance the characteristics of evolution and innovation, yet do so in a stable, controlled manner.

BESPOKE FEATURES

Another area of Control lies within customer-driven bespoke features. If a customer controls what you build, and that feature is bespoke (only suitable for that single customer), it may introduce significant additional complexity into a product (in the form of Technical Debt), slowing an entire business, and thus affecting your bottom line. You may - for instance - end up:

- Embedding bespoke code alongside the core product, but build/deploy different versions of the same product for each customer - a form of pollution.

- Polluting an entire deployment pipeline with bespoke features (for instance, building a bespoke executable, then executing bespoke tests against it), slowing releases for everyone else.

- Creating a (Git) branch per customer, further polluting deployment pipelines, increasing delivery effort, and (unnecessarily) duplicating bugs/fixes on every branch (or forgetting to, and applying a patchwork quilt of changes on different versions) in a vain attempt to keep all branches aligned.

DESIGN SMELL

Breaking the Open/Closed Principle in order to facilitate a bespoke change is a sign that something may be wrong (i.e. there’s a smell), either in the design of that area of code, or in the practice of introducing bespoke code into that feature in the first place.

CONTROL AFFECTS OPTIONALITY

Optionality (our ability to select from multiple different choices) affects our ability to Control a situation. If we have many options, we have good Control, whilst limited options limits Control.

FORMS OF CONTROL

I can think of several forms of Control relating to software products:

- Technology - shape the way the solution is built (e.g. Microservices), what it's built with (e.g. Python), and what it's built upon (e.g. Cloud).

- Product - what features are built, how they’re sequenced, and which stakeholders can shape the product roadmap.

- Partnership - a shared responsibility (and thus control) between multiple parties to influence a product’s direction/vision. Partners may also shape the product roadmap.

- Governmental/Military/Standards/Regulator - bodies external to your business can also influence what (and how) it’s built, tested, verified, and released.

- Distribution - influence how/when value is distributed to customers/users, or who are permissible product resellers.

- Customer - last but not least, is the (direct and indirect) influence that customers can have on a solution.

This can take several forms:

- Direct influencers with significant clout may - for example - shape your product roadmap.

- A group of small customers may influence a vendor more than a single one, so work together to focus change.

- Who a solution can be sold to. For instance, some customers form contracts to ensure any work done on their behalf is wholly owned by them so can’t be repackaged as a re-sellable product.

FUNCTIONAL INTERSECTION

In this section, I describe how the level of Functional Intersection affects the size of any integration effort with another system. A small intersection suggests a light touch, and indicates relatively little integration effort. A large intersection suggests otherwise, and you may get more than you bargained for. Crucially, it’s important to understand this impact prior to rescinding Control.

CONTROL, TRUST & REPUTATION

“You’re only as good as your last [project/job]”

Trust can take a long time to establish, but is easily lost. It is linked to Control.

To relinquish Control, you should first trust the other party (you wouldn’t hand over the keys to your new car to someone you didn’t know and trust, would you?). Yet I often find people too credulous to accept that an untested source can successfully deliver key capabilities (I also regularly see people repeat the same unsuccessful outsourcing strategy and expect different results). This stems from a toxic mixture of poor judgement, Affect Heuristic, and a sprinkling of Bias. Poor judgement can affect your Brand Reputation.

TRUST & CONTROL

The level of Control you’re willing to relinquish should (but doesn’t always, due to poor judgement) increase with Trust.

CAVEAT EMPTOR

The technology team were asked to build a new retrieve API endpoint (to compliment an existing capture endpoint) for external use. As was typical for the time, we found the team already overextended, and unable to meet the desired timescales.

The business engaged with an external supplier to undertake the work. As was common practice, they would implement the desired functionality (in a mutually-agreeable technology), and then deliver the finished solution (including source code) to us on time, enabling us to manage any subsequent changes.

So, we agreed on the requirements, documented and shared them with the supplier, and then returned to our own busy schedules. Weeks crept by, and we began noting both how little communication we’d had with them (excepting the occasional fob-off that all was still on track), and no clear sign of progress (e.g. no code commits). Growing increasingly concerned, we suggested more regular catch-ups, only to be rebuffed with the same positive response - all was on track.

Finally, the delivery day dawned, and we waited and waited for the promised solution. Eventually, frustrated by the awkward silence, we tracked them down, and were given the unhappy (but unsurprising) news. The solution was far from complete.

Our frustration was deep. Whilst the lack of working software was disappointing, our main grievance lay with the (intentional?) misdirection, and unwillingness to communicate the bad news. For weeks, the supplier had surely suspected that they would fail in their obligations, yet spoke not one word to us on the subject (instinctively we probably knew it too; but suspicion and explicit evidence are not the same thing). Following heated arguments, we shifted our own release date to give them more time. Better late than never, as they say?

They delivered a fortnight later. A brief validation of its functionality quickly proved its functional correctness. But the deeper we dug, the more issues it exposed. A code review surfaced maintenance issues with the code’s general structure and design. Not ideal, but at least it functioned? But more investigation uncovered further issues; it wouldn’t perform/scale in a production-like environment (e.g. ~20 seconds latency for a relatively small dataset lookup).

We cut our losses several volatile and unproductive discussions later, disillusioned by the whole experience, and out of pocket. In our eyes, the supplier’s reputation thoroughly discredited.

Whilst this story didn’t have a happy ending, it did teach me more around Control:

- Actions are worth more than words. Talking a good game, and playing it, are fundamentally different. What you’re sold, and what you given aren’t always the same.

- Be (overly) explicit, and over-communicate, particularly with untested external suppliers.

- Trust you instinct. If someone behaves unexpectedly, problems may lurk below the surface. Tackle them sooner rather than later.

- Whilst it’s important to give people an opportunity to right a wrong, if it’s going to fail, it’s better to Fail-Fast, than to fail slowly.

- Failure to manage Control can be a two-way street; i.e. some problems are of our own making; such as not defining clear boundaries to ensure the following is provided:

- Clear acceptance criteria.

- SLAs; e.g. performance and scalability expectations.

- Adherence to coding standards.

- Regular source code check-ins.

- Regular progress demonstrations.

Let’s consider the following examples of relinquishing Control in more depth:

- Partner introduction followed by a fail on their part.

- Handover and free reign.

PARTNER INTRODUCTION FOLLOWED BY A FAIL

Let’s say that you and I are already acquainted. We meet unexpectedly, and during our conversation I learn that you’re looking to get some building work done on your house. Luckily, I know a good builder, and give you the details. You employ that builder, who proceeds to knock down the wrong (supporting) wall. You’re - quite rightly - aggrieved with the builder for such a heinous act, but would you not also be annoyed at me for my recommendation? i.e. my personal reputation has deteriorated in your eyes.

If my earlier logic is sound, why should it be any different from the perspective of a business relationship? If I sell you a product that requires the aggregation of a number of different partner solutions, convince you to trust businessB to deliver part of that solution, but businessB does a poor job, might you not also (rightly) heap some of the blame upon my shoulders? I did introduce them to you after all. The trust that you’ve tried so hard to build up with the customer has deteriorated, tarnishing your reputation.

HANDOVER AND FREE-REIGN

Consider another example. Your business supports a number of core features in their existing product. These features have been important (the Crown Jewels, so to speak) factors that have (and continue to) enabled sales. Now let’s say you’re business decides to reconsider its position with regard to those features (maybe they’re looking to pivot), potentially eyeing third-party integration alternatives instead. Maybe the feature is difficult to manage, or requires significant change that the business has little capacity for.

Should you consider relinquishing Control? Sure, but let’s consider a few scenarios.

Forget for now about the technical feasibility of the integration. What about the implications to your brand? If you push this responsibility onto a third party, are they (or could they become) a competitor? Additionally, put yourself in the customer’s shoes; what incentive do they now have to come to you, if the core of what you’re known for is a simple wrapper to another party’s solution? Can you still position (and market) yourself as a believable specialist to prospective customers? Might your existing customers renegotiate with the new supplier instead?

THE CONTROL QUADRANT

Whilst the figure below is just one opinion, I think it is a useful heuristic to better understand the level of influence you can expect. See below.

Example Control Quadrant

Ownership sits upon the X-axis, whilst Influence rests upon the Y-axis. High ownership and high influence (top-right) indicates a high level of control (you can build roadmaps, implement features, sell it independently of other partners etc etc); however, this has coordination costs (e.g. the need to coordinate all those specialisms that may not sit well with the business), management costs, and you must also have a vision. Conversely, anything around the bottom-left indicates limited ownership and/or directional influence.

Let’s examine some of them.

AGGREGATOR

An aggregator is a party who builds (or aggregates) a set of products/services from other sources, into something valuable in its aggregated form. Aggregators don’t tend to build much functionality (they rely upon it), but are heavy on the integration front. Because they depend so heavily upon many others, there is a greater likelihood of change, and overall Control is generally quite low. I remember considering a form of aggregation for a prospective client by using an open-source content management system; however, the integration effort was so painful that it gained no traction.

ALL YOURS

A rare breed indeed, but if you’re in the enviable (or is it?) position to have complete control of everything, from hardware, platform, OS, software libraries, to the application stack - with no governmental or regulatory intervention - then (assuming capacity) you do pretty much anything you want. However, you’ll probably need to coordinate all of these activities, increasing cognitive load and staffing needs.

PARTNER SOLUTION

Depending upon a partner to deliver part of a solution removes some strain from your own business, enabling you to focus efforts on your business’ strengths. And whilst cognitive load may have lessened, there’s still a (a) coordination exercise to consider with a business you may have limited control over, (b) a potential reputational concern if the partner fails to deliver.

(USING A) SAAS PRODUCT

Leveraging a SAAS (Software As A Service) solution can be an (extremely) affordable alternative to building, or hosting, your own. The model requires minimal investment - it’s typically OpEx (monthly subscription), providing a great deal of flexibility in their pricing model.

Control can be good - you’ve the ability to trial an idea without a heavy investment, or commitment to the SAAS vendor. The potential downside is that the SAAS solution is probably highly productised (you get what you’re given), and you may suffer potential resource contention from other “tenants” (e.g. I’ve seen several well-respected SAAS products with a noticeable latency lag when their US end-user customers come on line in the morning and start using the system).

SMALL ORGANISATION USING PLATFORM

A small organisation that makes heavy use of proprietary platform technologies typically has no Control over what those foundations are, and when they’re released, and may have to juggle immediate change (when it comes in), and procrastination (deal with it later). You do - of course - have the Optionality to choose what you use, and what you discard, but only to a point.

OWNER, BUT NO CAPACITY TO CHANGE

You may be the product owner, but (for many reasons) have no capacity to change it. In this case, you must either better manage your manufacturing flow, or look to others to can satisfy the requirement; i.e. you find a way to Control the flow into your production system, or you request the help of others (losing some Control) to achieve your goal.

CONTROL CULTURE

Instilling the right cultural ethos early on also sets a precedent for how future interactions should take place; for example:

- How should you communicate? Through some formal approach like design reviews, ad-hoc discussions, or something else?

- How often should you communicate, and through which medium(s)? e.g. whilst messaging tools are great for short conversations, there is always ambiguity and distortions; conveying the minutiae may be better served through face-to-face discussions.

- What working practices are acceptable, and what ones aren’t? e.g. if you expect “continuous” practices to be employed, then ensure they are.

- Decision making. What type of decisions can be made independently, and which ones require wider group involvement? e.g. if you’re developing a solution that I will later assume responsibility for, then I’ll initially focus on agreeing the technology choice far in advance to any agreement around code structure.

- When, and how, are problems escalated? There are few things more frustrating than being told about a major problem but given no time to find a resolution.

QUESTIONS ON CONTROL

Below are some questions to consider around Control:

- Strategic:

- Does the solution involve partner interactions? How well do you know your partners? Have you worked with them successfully on other projects?

- Have you defined and agreed sensible SLAs? Have you involved all appropriate experts in the decision?

- Are you comfortable with handing over control of (potentially key) features to another party? In which ways could it benefit that business, whilst hindering your own? Credibility, for instance. Are they (or could they become) a competitor? Do they provide similar functionality to your own product. Will your existing customers migrate to them? Will it make them formidable, and thus less willing to fulfil your business’ needs?

- Are you building a product, client services, or something else? The chosen model should shape some of your decisions around who builds what (e.g. can you find other suppliers to build bespoke solutions?).

- If you opt to relinquish Control, will it make you more profitable both in the short and the long term? What do you gain, and lose, from it?

- Delivery:

- Who dictates when change enters your manufacturing system flow?

- (Put your pride aside) Who really controls your release cycle and delivery dates? You, or some external party(s)? Is that acceptable?

- Systems Integration:

- Where does your (customer) data reside? European customers may mandate it remains in Europe.

- What sort of secure practices are in place in relation to compliance (such as GDPR or PCI)?

- What’s the real integration effort of incorporating the new system? Not the biased system 1 view, but the considered view. Don’t sign until there’s been sufficient due diligence.

- Useability. Is the user experience seamless, regardless of the solution/system being used.

- How does the external system inform your system about changes in its state?

- If multiple systems can stimulate a notification event (e.g. a customer email), how do you (a) disable key notifications in one system and not the other, and (b) ensure the experience is consistent across them?

- Non-functional Control, such as Scalability. For instance, if you’re using shared services (typical of a SAAS model) will other customers introduce resource contention at a vital time for your business?

- Has the third-party concrete evidence of regular security testing (e.g. penetration/vulnerability threat modelling)?

- Is the entire solution built (and thus relatively stable), or is it still undergoing large-scale change?

- Is there a facility to simulate different events in the other system’s test environment, or must you build out your own simulation, solely to represent those scenarios? I’ve seen this problem often enough to no longer be surprised by it.

- Does the other party have the facility to execute performance/load tests? Again, I’ve seen enough examples where the supplier can only offer up a production environment for load testing, which is often unsuitable, and adds great risk.

SUMMARY

I’ve learned much from Control over the years. Firstly, that Affect Heuristic heavily influences many of us, to the point that we don’t always carefully consider every aspect of Control before pronouncing judgement. Highly influential people can unfairly Bias other’s opinions in these circumstances, leading to ill-considered decisions that can affect future business performance.

Secondly, whilst I certainly don’t advocate doing it all yourself if you need not (there be dragons; you should leverage other’s expertise when it makes sense to), it’s still important to be cognisant of the potential outcomes of handing off Control to another party (it’s rarely - as the saying goes - a free lunch).

Thirdly, I’ve learned the great importance of explicit (over) communication, particularly in situations where you opt to relinquish some Control. Some of the failures I’ve witnessed around Control could have been easily remedied if both parties had agreed to “guardrails”; i.e. they agreed and understood boundaries and acceptable parameters. It’s vital to iron out any areas of contention early (at project inception) so things are well understood by all parties; however, that doesn’t mean you can’t use JIT Communication, only that the critical aspects of a project are well understood early on.

It’s easy to see how a consumer can lose Control. Regular supply-chain changes can make it feel like you’re building upon quicksand, and lead to the perception that:

- Things malfunction unexpectedly. For example, the automatic upgrade of some browsers enables them to regularly deliver improvements, at the cost of sometimes breaking the applications that depend upon them and user interruption.

- It seems more fragile to users (if change isn’t well managed). This fragility isn’t necessarily accurate, however, it’s the perception of more regular failings that sticks in people’s minds (it’s more likely to affect frequent users) rather a single disaster, which may receive more press-coverage, but not necessarily be seen by the affected customers (e.g. the unlawful extraction of sensitive information from systems).

- Due to its unexpectedness, requires regular unplanned work, and thus regular Expediting. Whilst there’s some truth here, there are options; e.g. Agile enthusiasts often counter this by holding back spare capacity.

- Cannot be scheduled effectively. Don’t underestimate the criticality of this point, particularly in the eyes of businesses married to more conventional project planning activities. Regular change in areas outwith your control (such as the platform you build upon, or partner services) can make change difficult to foresee, and thus formally schedule.

So, why favour this model over the more conventional project-driven upgrade model? Like many things that lack a continuous flow of change, there’s a rude awakening at point of change (time of upgrade in this case). What may be frustrating, but potentially manageable if undertaken in-situ, is now frightening and potentially disastrous, carries significant risk, and may be wholly impractical. To me, Control is best managed by committing to many small increments of change (refactorings) that protects the health of both your systems, and thus, your business. To do that, there should also be some ability to limit Blast Radius (see Safety Net). Or, to use another analogy, upgrades are a bit like dental flossing. You may not like it, but your teeth will suffer if you don’t intervene on a regular basis. Regular intervention promotes longer-term health.

THE WHEN CAN BE JUST AS IMPORTANT AS THE WHAT

Change isn’t just about the what, but also about the when. If you’re constantly flooded with change but have insufficient capacity to manage it, you’ll regularly suffer breakages or staleness. It may also be a sign that your delivery model is substandard.

Finally, whilst I’ve attempted to show some areas that Control can influence, it’s rarely that simple, being shaped by many diverse factors. And even if you have complete ownership, if your key stakeholders are disengaged, then influence (and therefore Control) is low. Find out what’s important to your business (profit?), then shape decisions on control around that.

FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS