Culture & Mindset

SECTION CONTENTS

- Aesthetic Condescension

- Change Friction

- Mobbing, Pairing, & Indy

- Unit-Level Efficiency Bias

- Specialists v Generalists

- Bias

In this section I discuss the cultural and mindset shifts that I consider important to better align business and technology, and grow a business.

AESTHETIC CONDESCENSION

Humans are visual and tactile creatures, conditioned to grow affinities with aesthetically-pleasing products they can see and touch (Apple has done rather well on aesthetics). Consider the plethora of Unqualified Critics who’ll line up to provide their feedback on a new user interface (UI), in contrast to the focus a new API or back-end solution receives, and you'll soon realise the impact user interfaces have. UIs are far more accessible (Lowest Common Denominator), to a broad range of stakeholders, so they naturally receive more attention (even though they’re often not the most important).

A good UI can hide a lot. Even seemingly high quality products can suffer from significant technical deficiencies. One potential problem I’ve witnessed with beautiful user interfaces (UIs), is what that shiny new interface may hide below the surface (i.e. Aesthetic Condescension). To the uninitiated, an aesthetically pleasing interface may successfully hide (at least initially) deeper inherent system issues (e.g. it’s still a Monolith under the hood; or the UI interacts directly with the database, hampering scalability, evolvability, and reuse), and vital questions (such as stability, and regular refreshes) remain unasked.

The best metaphor I can think of is the elegant swan moving gracefully across the surface of the water, whilst (hidden from view) underwater, the little duck’s legs paddle furiously to propel it.

Whilst an aesthetically pleasing UI can be a big sales enabler, knowledgeable customers/investors will apply a more cautious, metrics-driven decision-making process as part of their due diligence. Remember the saying, beauty is only skin deep.

CHANGE FRICTION

Change Friction takes many forms. It is an unwillingness, or inability, to change or evolve something (particularly in relation to a product or area of a system) due to the obstruction of others.

Change Friction can stem from:

- Poor stakeholder confidence – one (or more) stakeholders have little confidence in the change, possibly due to a real/perceived complexity, the lack of risk mitigation (e.g. no automated testing), or even a lack of confidence in the overarching product.

- Blast radius – there’s no (easy) way to sufficiently isolate the change due to its rippling effect (e.g. significant regression testing, or whack-a-mole bug fixing). Blast radius can also impact evolvability.

- Educational – the benefits of the change are insufficiently described or understood. Communication cannot convey every aspect to others (partly due to Rational Ignorance), so we lose (potentially key) pieces of information that could be used to make good decisions.

- Time constraints – the change won’t be completed in time to meet a deadline.

- Cost constraints – the change will cost more than the key stakeholders are willing to spend.

- Resource constraints – the change is feasible, but there’s no one to undertake the work. Or, it requires a specialist skill that is difficult to obtain.

- Personality – the decision maker(s) doesn’t like the change agent.

- Political – there is some political aspect at play. Maybe there’s some empire building going on, or some envy; maybe there’s other changes afoot that can’t yet be promulgated.

- Goal oriented – the change doesn’t meet the business mission, or goals.

- Cultural – it doesn’t meet the cultural aspirations of the business.

- Outside influences – an external body (possibly governmental, or a supplier) prevents, or hampers, the change.

- Innovatory challenges – the real change involves creating (or using) innovative techniques or technologies that have not yet been trialled.

- Vendor Bias – the favouring of one vendor over another (often denigrating the other), regardless of the offering.

- Inculcation Bias – the habit-forming aspects of an individual, team, or business that are difficult to break.

COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE

At the most basic level, Competitive Advantage is whatever gives you the edge over your competition, and may include:

- Unique Sales Proposition (USP).

- Attractive Pricing.

- Fast Delivery (i.e. TTM).

- High Quality.

- Flexibility and agility.

COMPLEX SYSTEMS

Humans have a natural tendency to simplify everything. A intriguing area of learning that is gaining traction is the idea that complex systems cannot truly be understood or controlled.

When you pause and look around, you begin to see complex systems everywhere (and anywhere), from financial and political systems, down to how to successful sports persons interact with their environment.

Complex systems are difficult to understand, are often tightly coupled (where the previous unit of work feeds directly into the next), and tend to cause significant disorder to the owner when they fail. The tightly coupled nature of these complex systems often means that even a small upset/change upstream can cause significant (and often obscure and opaque) downstream consequences; i.e. a failing at one section can bring down the entire system. Tweaking just one part of the system can have a positive, or negative, bearing upon the entire system.

Let’s look at an example. You might not consider a golf swing complex (unless you play the game). However, let’s break it down into its constituent parts:

- The “Waggle”.

- Address.

- Takeaway.

- Backswing.

- Top of Backswing.

- Downswing.

- Impact.

- Release.

- Follow-Through.

There’s also further complexity around stance, grip, tempo, timing, swing plane, wind speed etc. Even the professionals have found out; get any part wrong, and the entire system fails... There’s too many competing factors at play to control all eventualities. I’d call that a complex system!

NETFLIX & COMPLEX SYSTEMS

Netflix are renowned for their focus on resilience, and the techniques (e.g. Chaos Monkey) they intentionally use to test their systems resilience. So much so, that (at appropriate times of the day), they intentionally inject failures into their production systems to then apply Continuous Experimentation practices. They’ve learned to trust resilience over control.

CONTINUOUS EXPERIMENTATION

“I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” – Thomas Edison

The most forward-thinking companies leverage Continuous Experimentation to learn, and evolve, quicker than their competition (offering a Competitive Advantage). Continuous Experimentation enables individuals and teams to undertake many small iterations or trials (whether it be a new technology, design, or practice), learning from each whether it is (a) valuable, and (b) fits the company’s needs, culture, or ethos.

Continuous Experimentation also involves a mindset change to embrace failure. Why? Failure tends to be our greatest teacher (isn’t it the best way to learn?). Often, by learning from failure, we are guided to success.

To enable people to successfully experiment, you probably first need to employ a Safety Net.

CULTURE POLLUTERS

As the name suggests, Culture Polluters are individuals who don’t subscribe (intentionally or unintentionally) to a business’ ethos. These individuals may be aggressive, despondent or disinterested; they may also be some of your most talented staff. If not carefully managed, they tend to zap the culture of its strength.

Culture Polluters may not seem harmful, but their actions often affect others, and sometimes imply to those others that this manner of behaviour is acceptable (causing the snowball effect).

DELIVERY DATE TETRIS

“In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.” – Dwight D. Eisenhower

Tetris (if you’re unaware) is a puzzle-based game, where you attempt to combine different shaped moving blocks together to score points. Delivery Date Tetris is the equivalent approach for software deliveries. In this approach, work is fit around delivery dates, rather than (necessarily) the needs of a product.

The main problem with this style of project management is twofold:

- Expediting; it’s driven almost solely by the customer’s dates, and therefore is at the whim of whoever shouts the loudest (the expeditor becomes expedited). Typically, you commit to one customer deadline, and then another customer shouts louder, forcing you to replan it all over again, but to now fit both customer’s dates.

- You’re less focused on feature value, and more upon delivery dates (i.e. mindset is date-driven rather than value-driven). It quickly becomes impractical and unsustainable (you’re just shuffling work items around to anywhere they’ll fit, rather than trying to prioritise them by value, importance, or risk).

Once you realise you can’t meet these time demands, you start looking around for alternatives. Unfortunately, one such option (revisiting The Iron Triangle) is to make quality the fall guy (Quality is Subjective), potentially to the detriment of long-term sustainability.

DESTRUCTIVE BIAS

Everyone has Bias; some is positive, some negative (or destructive). Destructive Bias is often irrational, and limiting. It’s dangerous because it blindsides people’s common sense, creating a narrow-mindedness that affects decision making.

Destructive Bias may – for instance – cause individuals to favour the needs of an individual or team (particularly silo’d teams with clout) over the needs of an organisation. I’ve also noticed a technology bias with many Linux evangelists I know towards anything Microsoft – some go out of their way to denigrate anything they do. This is a platform or Vendor Bias.

Destructive Bias can cause political infighting, a common cause of a fractious culture.

It is particularly important for architects to offer balanced guidance (the best ones I know don’t limit themselves to one vendor, framework etc); to do so, it’s important to remain open-minded, and successful identify and manage any internal bias.

FUNCTIONAL MYOPICISM

Functional Myopicism relates to an unhealthy focus on functionality, to the detriment of all else, including non-functional or delivery needs. Sustained use of Functional Myopicism can be extremely debilitating to a business, and typically leads to Technical Debt, and slowdown (Cycle of Discontent).

Myopicism can take many forms. For instance, I’ve witnessed an unhealthy focus on TTM and ROI, to the detriment of Quality (Sauron’s Eye of TTM). There’s also (to name a few) Uniform Solution Myopicism (where every problem is solved the same way), Vendor Myopicism (always use the same vendor, regardless of alternatives), and Framework Myopicism (which is just a play on Same Solution Myopicism).

Sprint work provides one indicator of the degree of Functional Myopicism. Are your sprints always filled with features and rarely any non-functional work? That’s probably Functional Myopicism. I also argue that undertaking Cleanup Sprints every n iterations is a Functional Myopicism smell (it’s too easy for the business to pull the cleanup sprint, for the supposed sake of the big functional push).

INAPPROPRIATE ATTACHMENT

Inappropriate Attachment is linked to Bias, and can cause poor decision making.

Inappropriate Attachment is the concept where people become overly attached (and therefore biased) towards something (e.g. a project or product) that (now) has lost its perceived value. It’s a state of mind, typically caused by the significant investment of money and/or time, that impels people to complete the journey, regardless of the wasted spend. Inappropriate Attachment is sometimes caused by Individual Perception – the stakeholder(s) most responsible sees any failure as a personal branding failure, and become emotionally attached to its completion.

INCULCATION BIAS

Inculcation Bias, being biased through the act of repetitive habit, is one of the toughest aspects likely to cause Change Friction. Basically you teach yourself to behave in a certain way, through repeatedly performing the same actions, until it becomes second nature. Whilst this can make you highly efficient (David Beckham and Tiger Woods spring to mind), it can also lead to serious (cultural) impediments when change is required.

Let me offer you an example. I was once asked to review some new code written by a senior engineer to meet a new business requirement (the problem involved identifying the number of items the customer had, and using it to decide whether to permit them access to add another record). The engineer was fully aware of the existing product’s significant scalability problems, so I was taken aback when I saw the solution. Rather than using the power of the database, he had pulled out all of that customer’s records, storing them all in memory, then queried the number of records in the list (that’s all, nothing more). When I asked why he had done it that way, even though he was cognisant of our product’s inability to scale, he answered with, “because that’s how we’ve always done it”. That’s Inculcation Bias.

Now let’s consider an alternative case. One of the hardest aspects of stopping smoking isn’t stopping the act of smoking, but the habits that accumulate around it; e.g. surrounding yourself with other smokers, always smoking directly after breakfast or before bed etc. These are all difficult habits to break because they’re inextricably linked to how we function at an individual level (e.g. if one habit is to smoke directly after breakfast, then unless you stop eating breakfast, you’ll still encounter the desire until you break that habit).

JUST-IN-TIME COMMUNICATION

Just-In-Time (JIT) Communication is important for the following reasons. Providing too much information, or delivering it too soon, is inefficient – by the time the individual needs it, it’s either stale (something has changed and it’s lost its value), or it’s been forgotten and must be repeated (inefficient). Yet delivering tardy communications risks misalignment so (a) nothing is done, (b) the wrong thing is built, or (c) poor quality is introduced.

JIT Communication is a simple concept, but a difficult one to master. To successfully deliver information immediately prior to its need, you must prepare and vet it for accuracy, know who it must be delivered to, ensure they are available for its delivery, and assess the current level of knowledge of all persons who need it (in some cases, tailoring it to the audience). Sprint planning and backlog reviews are one technique to support JIT Communication; they prepare the system, and the people for the next work items.

Consider software manufacturing. Much of the system is about how (and when) information, or ideas, flow; not the realisation (the software) of those ideas. In fact, at a more philosophical level, isn’t the thing of value the idea, rather than the software (the software is just one form of realising the idea)? Reminds me a bit of Plato’s Theory of Forms. Anyway, enough introspection...

KNOWN QUANTITY

A Known Quantity is a very powerful idea, and is typically relates to Uniformity and Consistency. Known Quantity suggests two things:

- A low likelihood of Surprise, which is generally good in software.

- General efficiency gains.

A Known Quantity often displays the following qualities:

- Easier to sell. The sales team are well versed in the product, know any quirks, and can easily leverage it to customer needs.

- It is easier to find, change, deploy, and run software as it’s all built the same way.

However, to counter my own argument, an Inefficient Known Quantity should be discontinued.

MANUFACTURING PURGATORY

The silo’ing (Siloing) of people is one prevalent cause of Manufacturing Purgatory – where work items are left in a waiting state, until a resource becomes available to work on it (i.e. to add value). Manufacturing Purgatory is a lonely place; the longer something rests there, the less value it has, the more it interferes with other work items, and the more that entropy sets in. Continuous practices are commonly used to mitigate Manufacturing Purgatory.

OVERPROCESSING

Overprocessing is one of The Seven Wastes, and relates to the human desire to refine, ad-infinitum. You might also know it as Gold Plating. Engineers are renowned for their perfectionism, even to the point of Diminishing Returns; where there is no valuable return to be gained from further refinement. Beware of perfectionism, but ensure there’s still a fair balance between perfectionism and the accrual of Technical Debt.

QUALITY IS SUBJECTIVE

Although, quality may be subjective is a more accurate definition, it doesn’t possess such a potent headline... This one is best explained with a story.

Let’s say you’ve agreed to undertake a contract to build some new software for a customer. Things begin well, but a few months later it starts to go awry – there are myriad things that can cause this, but let’s say that insufficient time was allowed to undertake a technical due diligence, and a key concept is unworkable in the assumed manner (assumed is the key word here), when the contract was drawn up. What options are open to us?

We can:

- Renege on the deal, incur any costs associated with our contractual obligations, and (potentially) suffer reputational damage to our brand, or,

- Ask for more time and/or money; this is possible but unlikely, and also has brand reputational implications, or,

- Undertake the work, but soak up the costs internally, and (hopefully) learn our lesson, or,

- (unfortunately) View quality as a mutable (and subjective) quality.

The figure below shows an specialised version of the Iron Triangle (described earlier).

The Iron Triangle with Object/Subjective attributes

Note that I’ve extended the concept to indicate the objectivity (or ease of measurability) of each attribute (green is objective, red is subjective). Whilst Time and Cost are generally objective, empirical, and (reasonably) easy to measure (“oops, that’ll push us over budget!”), Quality may not be.

One person’s view of quality may (and often does) differ radically from another. And even when there’s consensus, quality covers such a broad and diverse spectrum, that accurately measuring it in its entirety is highly challenging. In fact, we often we end up measuring Perspective instead.

REACHING A QUALITY CONSENSUS

Reaching a consensus across multiple parties can be extremely challenging. Often, things are left unsaid, remain subjective and thus unmeasurable, and return to cause future problems. The cause is generally incorrect assumptions.

There’s another consideration too; a customer may not understand quality within the domain (e.g. software). Often, a customer specializes in a particular business domain (e.g. retail, banking), not in software construction, and can’t recognise good quality software (Rational Ignorance).

To offer up another analogy, some time ago I bought a new door (and surroundings) for my house. We chose a high quality (and reasonably expensive) door from the showroom, which also included fitting. When it was fitted, the door was fine, but the surroundings (I felt) were hastily and sloppily done. Although I didn’t complain (I didn’t feel I had sufficient domain knowledge to do so), my concerns were later founded when a strong wind blew a cold draft of air through one of the poor fittings.

The moral of the story? The fitter’s Perspective of quality differed from mine, and even though I was no expert, I knew enough to understand quality in a domain I had no real expertise in (and that I should have believed in myself more).

Now, the door company got their money, but they will never see another penny from me. Their short-sighted treatment of quality as a second-class citizen has undermined their Brand Reputation in my eyes, and is unsalvageable.

EVEN SOFTWARE VENDORS GET QUALITY WRONG

You might think this wouldn’t happen with the well-established “software” businesses, but I’ve worked with several vendors (including one industry heavyweight) who’ve supplied solutions that were (at least by my standards) well below quality expectations. I’ve also been on the receiving end, when we were forced (against my better judgement) to deliver a solution we knew to be below par, but had no influence to change; very demoralising.

Because quality can be notoriously difficult to agree and measure, some parties base their quality decisions on trust; e.g. customer A trusts vendor B to deliver a robust solution (there seems to be a good number of big-vendor contracts signed on trust that fall well short of expectations). To me, trust isn’t a good stand-in for quality, and can place the customer (and possibly the vendor) in a precarious position. It entices an unscrupulous vendor to behave in a manner that may be at odds with the longer-term strategy of both parties, so:

- The customer doesn’t get what they expected, and,

- The vendor may become complacent around quality, and have a rude awakening when the customer finally realizes where the problem lies.

RATIONAL IGNORANCE

From around the medieval ages, all the way up to the enlightenment, we labelled a select group of intelligentsia as polymaths (much learning). In those days, although we knew about maths, physics, biology etc, it (typically) wasn’t what we’d class today as deep knowledge (there was/is still much to learn). This enabled (smart) people to study many different branches of learning and still be labelled an expert.

This is rarely true nowadays. We’ve moved from generalists to specialists, mainly because as humanity grew our understanding in each field of study, it became increasingly impractical to deeply understand multiple disciplines (the so-called 10000 Hour Rule). So, we grew to be single discipline specialists.

This need to specialise has led to Rational Ignorance; our internal tacit agreement, due to finite time pressures, to choose what to learn. Rational Ignorance is one of my primary drivers for writing this book. Although few can be experts across both business and technology disciplines (not me), we can still (with relatively little effort) increase our awareness and better engage with other stakeholders.

RAVENOUS CONSUMPTION

The internet (and technology) is a both a blessing, and a curse. It’s a great business enabler, allowing the wide and rapid sharing of information, ideas, and services (even internationally), but it’s also spread Ravenous Consumption – ruthlessly expectant consumerism; we are more judgemental of poor or late services.

Ravenous Consumption has forced change, at a great pace, upon everyone, including traditionally conservative businesses, who must learn to quickly evolve, or die. Were I to wager upon one of the established order’s greatest fears, I’d opt for their inability to outmanoeuvre the growing army of nimble startups that can swiftly learn, and evolve. These startups continue to eat into the profits of the established order.

REGRESS TO PROGRESS

We’re often in such a rush to deliver (Ravenous Consumption) that we fail to see the problems we’ve introduced. Sometimes we must Regress to Progress.

Although today the Leaning Tower of Pisa is viewed as a tourism triumph, it is an architectural flop, simply because the foundations were insufficiently established at inception. Through the years, they tried a number of tricks to right it (it was left alone for almost a century in the hope of stabilising it), and invested significantly more than was usual for an equivalent tower, but it was never successfully used it for its original purpose.

Sometimes, pressing on with a software product’s known limitations is harder than pausing to consolidate, or rectification (many businesses who’ve stuck with a complex Monolith probably know this already). The number of problems created by poor software quality can be many times more than the cost of regular Refactoring (or even a rebuild). Under these circumstances, beware of Inappropriate Attachment – if something is poorly implemented, it’s prudent to fix it sooner rather than later.

REWORK

Rework is one of The Seven Wastes (it’s sometimes classified under Defects). It is costly due to the inefficiencies it causes (mainly in delivery flows), and it is exacerbated the longer a feature sits in Manufacturing Purgatory. Rework might (for instance) be caused by a defect, or a communication failing, causing the wrong thing to be built, or some non-functional failing (e.g. a security failing).

Let me elaborate. Let’s say you work as a software developer, and are required to build a new business feature (let’s call it feature 1). You’re given the right information, at the right time, to complete your task. You write your unit tests, then code the solution, before committing the changes to the source repository, then update the ticket for admin purposes (i.e. all the typical lifecycle actions). Due to the unavailability of a tester (let’s say the sprint capacity wasn’t well managed), the feature now sits in Manufacturing Purgatory. You then immediately select another ticket from the sprint backlog, and begin work on it.

Some time later, a tester (Bob) becomes free, picks up your ticket for feature 1, and begins testing it. Bob spends a day at it, but eventually identifies a major bug that will prevent its release to production. Bob returns the ticket to you; however, you’re busy with feature 2.

Now here’s the dilemma. If you remain working on feature 2, we have Inventory clogging up the manufacturing flow, and reduced cash-flow (feature1 only accumulates value once it’s released to the customer). However, if you’re taken off feature 2 and switched back onto feature 1, then you’re performing two Context Switches (one to stop, remember feature 1’s original context, then fix it; the second to switch back to feature 2). This has productivity, and thus ROI implications.

The ramifications of Rework multiply the longer delivery takes, or the later problems are identified in the lifecycle (in some cases, IBM found that bugs identified in production are six times more expensive to fix than those found during the development phase).

SAFETY NET

The idea of a Safety Net is to provide the air cover (or an aegis) that enables an individual, team, or organisation to continuously experiment (Continuous Experimentation); a key feature for innovation, and results-driven outcomes.

Safety Net relates to Stakeholder Confidence. It’s a mechanism, practice, or technology, that drives the Stakeholder Confidence, by enabling the stakeholder(s) to make changes, or innovate, with relative impunity.

OTHER FORMS OF SAFETY NET

To achieve greatness, we must continually push the boundaries of our own abilities, by working at the very edge of what we currently think achievable.

Trapeze artists and tight-rope walkers use a Safety Net (in different guises) both as a way to improve (each attempt - even a failed attempt - marks an improvement, until what once seemed impossible is now attainable) and as a means of protecting themselves from the inevitable failures that occur when operating at the edge. These artists understand the inevitability of failure, but don’t fear it, and use it as a catalyst for advancement. In this sense, software engineering is no different.

Examples of Safety Net include:

- High quality tests & test coverage – at unit, acceptance, and performance levels.

- Microservices – encapsulation of a domain behind a stable (REST) interface enabling fast evolution.

- Collaborative Cross-Functional Teams.

(the) SEVEN WASTES

The Seven Wastes is a well established classification/categorisation of muda, the Japanese term for waste. It establishes seven criteria identifiable with waste.

You can remember them using the mnemonic, TIMWOOD:

- (T)ransportation – the unnecessary movement of goods or raw materials to undertake value adding activities.

- (I)nventory – raw materials, or work-in-progress that’s not been delivered to the customer.

- (M)ovement – the unnecessary movement of people to undertake activities.

- (W)aiting – goods or parts waiting for value-adding activities to be undertaken.

- (O)verprocessing – refining too much, or building things that aren’t needed (right now).

- (O)verproduction – making too much of something.

- (D)efects – I labelled this Rework. It means repeating something due to poor quality (or entropy).

You will find references to these wastes sprinkled throughout this book.

SHORT-TERM GLORY

Short-Term Glory relates to satisfying short-term tactics to meet impending timelines or budgets, and (realistically) sacrificing long term goals and strategies.

What’s particularly insidious about Short-Term Glory is the feeling of satisfaction it gives you. Resolving an impending customer issue before it becomes one can almost be euphoric, and can easily become a habit, but it doesn’t explain how you were verging on disaster in the first place...

Remember, tactics are not strategy, and if injudiciously used, may cause long-term problems.

SILOING

The silo’ing of people is a common cause of complaint and concern, within many established organisations. In this model, a person is grouped according to their skills and knowledge, and placed in a team of similar ilk; e.g. the “Development” team, the “Data” team, the “Operations” team. See the figure below.

Silos creating a Manufacturing Purgatory

In this type of team organisation, we have pools of staff; e.g. developers (the DEV team), operations (the OPS team) etc. Completed work items sit in a Manufacturing Purgatory, whilst they await another team to action it; sometimes it’s immediate, but often, that next team is constrained, and must complete their existing work-items before accepting more work.

I view these silo’d teams as workstations in Goldratt’s The Goal (I highly recommend it if you’ve never read it). Work items build up at whichever silo’s are “constrained”; the most constrained workstation slows the entire production line down to its own capacity.

Silo’ing can cause the following issues:

- A lack of transparency, collaboration, ownership, accountability, and Inappropriate Attachment. Typically, this approach pushes specific activities onto specific skills-based teams (e.g. Ops does all monitoring; Developers are blind to it, and can offer no support/improvements).

- Quality is not introduced early enough. Building quality software is a highly challenging task due to all the varying considerations and viewpoints. By neglecting to involve all stakeholders early enough, you run the risk of delivering a substandard solution (or worse, one with zero value). How many times have you seen a Developer’s ear bent by Security, Test, or Ops practitioners because they weren’t involved in the decision-making, and an important aspect has been neglected?

- Rework is a common practice. See my earlier point on quality.

- Inefficiencies. If rework is required, then the individual responsible for it may be busy on another task (technology staff don’t tend to spend much time twiddling their thumbs), or may have forgotten all about it, and must re-acquaint themselves with it.

- It doesn’t work, provide value, or deliver what’s been asked for. Remember the Agile practice of involving stakeholders early and often? It’s mainly to ensure the right thing is delivered, or to pivot if not. This is harder to achieve in silo’s.

Recent years have witnessed a strong backlash against the organisation of staff around silos (mainly stemming – in the software industry – from the Agile and DevOps movements). DevOps, for instance, is about cultural change; achieved, in part, through practices such as Cross-Functional Teams. By sharing information (at the appropriate time – Just-In-Time (JIT) Communication) with a more diverse audience (e.g. Customers/Product/Operations/Developers/Architects/Testers), we empower the team to own the entire quality lifecycle (from business requirements, to implementation, to operational use) of a solution, with early and regular group involvement.

And more diverse teams promote:

- Higher autonomy – less need to obtain feedback from other silos/individuals, where wait time is a factor.

- Greater team cohesion – they’re all aligned to common goals/strategy.

- Faster feedback cycles and decision making – the team has sufficient understanding, and diverse skills and knowledge, to make better judgements, sooner.

- Happier staff!

STAKEHOLDER CONFIDENCE

Stakeholder Confidence is one of the most important aspects of a software product. Key stakeholders with little confidence in the product, software, surrounding components (e.g. delivery), and practices (e.g. installing Agile practices in a traditionally Waterfall environment), will never truly support it (even if they say they do). These stakeholders influence others, until we reach the event horizon (there’s no return), and the entire product expires.

Safety Net can help promote Stakeholder Confidence.

SURPRISE

Surprise within the context of software is generally execrated. Typically, it suggests weeks of rework, or discovering a failed assumption that may halt a project or feature.

Remember, product development is just a form of betting – and with all bets, there’s often a surprise (often affected by Assumptions), and no guarantees. Even with a host of metrics at your disposal, it’s still a Complex System, and you’re betting on the success of a feature!

We can limit surprise using some of these techniques:

- Business Metrics on likely success.

- Ask the Customer what they want.

- Relative Sizing (i.e. comparative estimates).

- Uniformity and Consistency.

- Reuse.

- Test-Driven Development (TDD).

- Safety Net.

- DevOps, Continuous Practices, and Cross-Functional Teams.

TAIL WAGGING THE DOG

The idiom “the tail wagging the dog” relates to an undesired inversion of control between a master and subordinate, and is a concerning aspect I’ve witnessed within several businesses.

“tail wagging the dog.”

Definition: “—used to describe a situation in which an important or powerful person, organization,

etc., is being controlled by someone or something that is much less important or powerful” - Merriam-Webster.

To be clear, in this model, the impetus for business change and direction is driven from the servant to the master. For instance, in many technology-oriented businesses, it’s quite common for the technology department to gain such prominence that it drives the business in the direction it believes the business must travel.

The danger here is myopicism and Bias. Every organisation is composed of a diverse group, with myriad skills and business expertise, including operations, finance, accountancy, marketing, and sales; i.e. business groups directly responsible for generating profit, and safeguarding cash-flow.

And whilst a technology department should have a big say in the direction a technology business travels, should they dictate it? Are technologists (in the main) given adequate and accurate information, and have the skills and knowledge (and interest), to make sound business decisions over an extended period? Do they understand the market and your competitors, or might they only address the issues of the business as they see it?

Whilst it is sometimes necessary for one department to dictate business direction, it sets a dangerous precedence that they won’t (or can’t) relinquish control. It’s also habit-forming. People have a natural aversion to challenge powerful entities, or people, which sees the tail gain more power, and the dog lose its teeth.

How might businesses find themselves in this situation? It could be through losing focus, an unwillingness to tackle systemic problems, a lack of Technology Consolidation, poor assumptions and decision making, functional myopicism, cultural, or when the business lacks the technical expertise to resolve crippling Technical Debt.

Before I get accused of unfairness, or you get the wrong impression of technologists, please note that the situation is often the result of necessity, rather than desire (I realise Caesar used this ruse). As the old adage goes; some have power thrust upon them. I’ve witnessed these situations, particularly when an organisation rests on its laurels, focuses too heavily on functionality (Functional Myopicism), and forgets to innovate; or accumulates a mountain of technical debt that hampers their competitiveness. But I’ve also witnessed the great professionalism of those technologists who realise the long-term dangers of this inversion of control, and find ways to re-engage with key business stakeholders to become the decision-makers.

To conclude this section, I’d like to offer the following thought-provoking idea. Fact. Technology is a fast-paced, constantly-changing environment. Like it or not, this gives technologists a strong advantage over the more conservative business groups. In this scenario, the Inculcation Bias of constant change exposed to technologists on a daily basis actually makes them strong proponent for change (regularly required for business competitiveness), which is (I suspect) why you may see regular occurrences of technology wagging the business...

FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS

TTM MYOPICISM

Over the years I've witnessed various types of myopicism. One of the most destructive being a narrow-minded focus on TTM.

In this case, I found a business so focused on TTM (Delivery Date Tetris), that they forgot about many of the other vital qualities required to build a reliable software product (I’m not saying TTM isn’t important; I’m saying balance is more important). The result was a de-emphasis on quality, leading to the Cycle of Discontent.

UNQUALIFIED CRITICS

Unqualified Critics are the outspoken individuals who will offer opinions on almost anything, regardless of their qualifications. Unfortunately, there’s no shortage of these individuals.

A common watering hole for Unqualified Critics lies with user interfaces (UI). Humans are visual and tactile creatures, conditioned to grow affinities with aesthetically-pleasing products they can see and touch. Consider the plethora of Unqualified Critics who’ll line up to provide their feedback on a new user interface (UI), in contrast to the focus a new API or back-end solution receives, and you'll soon realise the impact user interfaces have. This phenomenon also relates to "Bike-Shedding".

Unqualified Critics come in many forms. The ones to fear of are those that hold sway over decisions based upon their “elsewhere skills”, or social standing. Some are not necessarily technically adept to criticise technical work, but are very good communicators and logicians. Some are extremely good technicians, but are unable to apply context to their criticism (e.g. label a work as poor, without considering the pressures/constraints placed upon others). Some might simply be the HiPPO (Highest Paid Person), unwilling to show their ignorance publicly, but able to use their political or social standing to influence criticism around their thinking.

INFLUENCED BY UNQUALIFIED CRITICS

Whilst it’s important to listen to as many viewpoints as sensible, we should be cautious of being over-influenced by Unqualified Critics.

Whilst Unqualified Critics are not necessarily Culture Polluters, I do consider them to be more prevalent within that category.

FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS

“BIKE-SHEDDING”

“Bike-Shedding” is another term for the Law of Triviality. [1] It relates to our inability to contextualise complexity (Value Contextualisation, Complex Systems), so we focus on what we can understand - the unimportant aspects.

“Parkinson's law of triviality is C. Northcote Parkinson's 1957 argument that members of an organization give disproportionate weight to trivial issues. Parkinson provides the example of a fictional committee whose job was to approve the plans for a nuclear power plant spending the majority of its time on discussions about relatively minor but easy-to-grasp issues, such as what materials to use for the staff bike shed, while neglecting the proposed design of the plant itself, which is far more important and a far more difficult and complex task.” [1]

I feel this law has some credence. We spend a disproportionate amount of time discussing the simple (choosing which colour to paint the bike-shed), rather than the complex (ensuring the nuclear reactor is correct and safe). For example, consider the plethora of Unqualified Critics who’ll line up to provide their feedback on a new user interface (UI), in contrast to the focus a new API or back-end solution receives. This fits into both “Bike-Shedding”, and Aesthetic Condescension.

A good UI can hide a lot. Even seemingly high quality products can suffer from significant technical deficiencies. One potential problem I’ve witnessed with beautiful user interfaces (UIs), is what that shiny new interface may hide below the surface. To the uninitiated, an aesthetically pleasing interface may successfully hide (at least initially) deeper inherent system issues (e.g. it’s still a Antiquated Monolith under the hood; or the UI interacts directly with the database, hampering scalability, evolvability, and reuse), and vital questions (such as stability, and regular refreshes) remain unasked. In these cases we’re in danger of “Bike-Shedding” over some very serious concerns, simply because we're unable, or unwilling, to sufficiently contextualise them (Rational Ignorance).

FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS

- [1] - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Law_of_triviality

- Aesthetic Condescension

- Value Contextualisation

- Complex Systems

- Antiquated Monolith

- Rational Ignorance

CONTINUOUS DELIBERATION

Picture the scene. You’re sitting in the fifth meeting of the week on the same subject. Everyone is frustrated, not only with one another, but with the subject at hand. This specific topic has been deliberated over for many months, and still there seems no end in sight. You’re in a perilous embrace with Continuous Deliberation.

Seems far-fetched doesn’t it? Yet, I can think of several examples.

Businesses can spend years ignoring problems. Let’s say your existing product is past its prime (on the tail end of the product life-cycle). There is a lack of Stakeholder Confidence (e.g. many developers shudder with horror at the prospect of maintaining it), yet the business still clings on to the possibility of extending its lifetime far into the future. Rather than tackle the problem head-on, they sit on the fence (for years), or compromise (Never Split the Difference [1]), making some small inroads, but never really investing in a product modernisation (which will be painful, costly, and time-prohibitive). Of course it’s entirely understandable - there’s no easy way forward. Meanwhile the industry is changing, evolving into something different, something more dynamic, with new competition blossoming from unexpected seeds. Time is a worthy opponent; your business’s Continuous Deliberation has the unsatisfactory outcome of “too little, too late”.

I’ve also witnessed several examples of Analysis Paralysis. For instance, I’ve seen an Agile team become paralysed by a (somewhat irrational) desire to consider every possible aspect of a problem (domain), to find the best way forward (Paradox of Choice), rather than selecting an approach, attempting it, and then learning from its outcome. Let’s call the project Project Paralysis. This approach forced the team down a Waterfall methodology, mainly because they were too concerned about building the wrong thing. Instead, months were spent analysing a problem that - as it became increasingly clear - could never be fully comprehended (using the approach). The domain was too complex (Complex System), and problems were still being identified long after the project’s intended completion.

THE TRAP

The trap - in this case - was to over-analyse a highly complex and incomprehensible problem, and await its results, rather than doing something, learning from it, and letting it guide next actions.

WHY PROOF-OF-CONCEPTS?

We use Proof-of-Concepts (PoCs) to remove doubt, caused by:

Proof-of-Concepts - therefore - are a means to help resolve Continuous Deliberation.

- Complexity.

- Unknown factors.

DECISIONS, DECISIONS, DECISIONS

It seems that the ability to make a decision relates to the number of available choices. Too few choices affects your Optionality, and your ability to Control a situation, whilst too many (The Paradox of Choice - [2]) can paralyze your ability to make any decision, and thus we fall into Continuous Deliberation.

COMPLEXITY

Complexity creates uncertainty, and is another cause of Continuous Deliberation. And making good decisions is difficult if there don’t seem to be any good answers.

The famous writer, Neil Gaiman, once remarked of writing (I’ve only retained the part relevant for this discussion, but the entire quote is available at the link below):

“...

Sometimes it's like driving through fog. You can't really see where you're going. You have just enough of the road in front of you to know that you're probably still on the road, and if you drive slowly and keep your headlamps lowered you'll still get where you were going.

...

And sometimes you come out of the fog into clarity, and you can see just what you're doing and where you're going, and you couldn't see or know any of that five minutes before.” [3]

This is often true of software projects and complex domains, and why accurately sizing effort, budget, or a completion date, is so difficult. Complex Systems abound in our industry, and the way forward is often unclear.

“I am the wisest man alive, for I know one thing, and that is that I know nothing.” - Socrates

In these circumstances, it’s tempting to stop your journey and wait for the fog to clear (but this might promote Analysis Paralysis). Yet if you keep progressing (albeit slowly), the way will soon be clear enough to make the next right decision.

BELIEVABILITY

Personally, I find someone far more believable if they admit their uncertainty about a complex project, but offer ways to remove that uncertainty, than someone who admits no doubt.

There are different ways to manage, or - in this case, sense - complexity. The Cynefin (pronounced kuh-NEV-in) framework is one of them.

Cynefin helps us to make sense out of complexity, not necessarily to understand it (yet), but to help us gain a better overall sense of a complex domain, or system, before suggesting resolution through an appropriate decision-making model.

Cynefin has four main spaces:

- Simple. Things in this space are ordered and predictable (there's an established cause-and-effect relationship). The way forward is exoteric, and is typically resolved through applying established Best Practice. The decision model is: Sense -> Categorise -> Respond.

- Complicated. Whilst things in this space are ordered and predictable (there's still a cause-and-effect relationship), they are less obvious, and resolution requires appropriate analysis or domain expertise. The decision model is: Sense -> Analyse -> Respond.

- Complex. The resolution is esoteric, unpredictable, and cannot be predetermined (there's no obvious cause-and-effect relationship, and the same input may produce different outcomes). Things within this space can’t be resolved through typical measures like analysis or domain expertise, but are learned through fail-safe trials and hindsight. The decision model is: Probe -> Sense -> Respond.

- Chaotic. Just do something, anything. There's no cause-and-effect relationship. The decision model is: Act (get out of here) -> Sense -> Respond.

I never realised it at the time, but the main problems exhibited by Project Paralysis (described earlier) were due to attempts to resolve Complex space problems using the wrong decision model (i.e. attempt to analyse our way out of trouble, using the Complicated model of “Sense->Analyse->Respond”, instead of “Probe -> Sense -> Respond”).

CONVINCING OTHERS

Another big part of breaking the cycle of Continuous Deliberation is in convincing others.

Often, this is a challenging job. Rather than adopting an extensive canvassing approach, I’d recommend employing Circle of Influence, initially to some of your key existing relationships. Like-minded people tend to be swayed (Herd Conformity) - contrary to Rational Ignorance - sooner. Ensure the circle truly understands the problem - it's pointless discussing solutions until those stakeholders are fully engaged in the problem. To do that, you should find ways for them to care:

“Only if we understand, can we care. Only if we care, will we help.” - Jane Goodall.

INFLUENCING OTHERS

Still, influencing people can be remarkably slow. Traversing the circles to reach a common consensus from every key stakeholder can take a long time. I’ve been in situations where the initial stimulus wasn’t realised for several years - a long time in an industry dominated by Ravenous Consumption.

If the business is expansive, deeply hierarchical, or your relationship with key stakeholders is weak or nascent, then you must also rely upon the strength of others, and their relationships (and thus, why they must care), within their Circle of Influence, to successfully influence others. If these relationships exist.

Trying to convince everyone in one foul swoop is likely to fail because:

- Not everyone values the same things (Value Contextualisation), so reacts to different stimuli and keywords.

- You must dilute your arguments into a common language that everyone understands.

- By attempting to satisfy everyone’s viewpoint, you satisfy no one’s - you can’t focus all your effort on the points that specific key stakeholders care about.

- And then of course, there’s Trust.

Understand what motivates them. How (badly) does the problem impact them? Tailor content to those stakeholders, find ways to communicate with them in their language (i.e. minimise technical jargon to non-techs), and use the medium that works best for both parties. Most importantly, make them care.

THE DIFFUSION MODEL

You don’t (and shouldn’t) need to convince everyone. From my experience, the more people involved in the decision-making process, the greater the likelihood for discord, and Continuous Deliberation.

Focusing on people with high credibility, or social standing, within the business, can take you a long way towards convincing others - by allowing those new converts to influence others (Diffusion Model).

Note that I'm not advocating that you limit your circle solely to people you know (or trust) - you still need enough diversity to be challenged, or to improve an initial idea, but overloading it with uninformed or biased skeptics is a job for later.

SUMMARY

Businesses can spend years ignoring a problem. Given a difficult decision, some will procrastinate, spending years skirting around it rather than tackling it head on. Other tensions will gain traction, whilst some important decisions may be (unfairly) demoted. Whilst a healthy business should always have multiple tensions, they may enforce a practice of Continuous Deliberation on critical issues.

Analysis Paralysis is one form of Continuous Deliberation. In an attempt to understand everything, down to the last minutiae, we may hinder our ability to progress; to learn through doing.

Thankfully, there are sense-making frameworks, like Cynefin; powerful tools to make sense out of complexity. Rather than investing unwisely on the wrong decision-making approach, we can match specific problems to appropriate resolutions. For instance, if it’s complicated, we might ask for deeper analysis, or domain expertise; whilst we may opt for fail-friendly trials on complex problems.

FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS

- [1] - Never Split the Difference: Negotiating as if Your Life Depended on It (Chris Voss, Tahl Raz)

- [2] - The Paradox of Choice

- [3] - Neil Gaiman Quote

- Cynefin Framework

- Complex Systems

- Circle of Influence

MOBBING, PAIRING, & INDY

Suggested reads: Work Item Delivery Flow, Shared Context

"A good falconer releases only as many birds as are needed for the chase." - Baltasar Gracián. [1]

The construction and delivery of software is achieved through one of three common approaches:

- Independently (Indy) - as in solo development, testing, and review activities.

- Pairing - such as a pair of developers, or a developer/tester pair.

- Mobbing - as a group of people (often with very different skills).

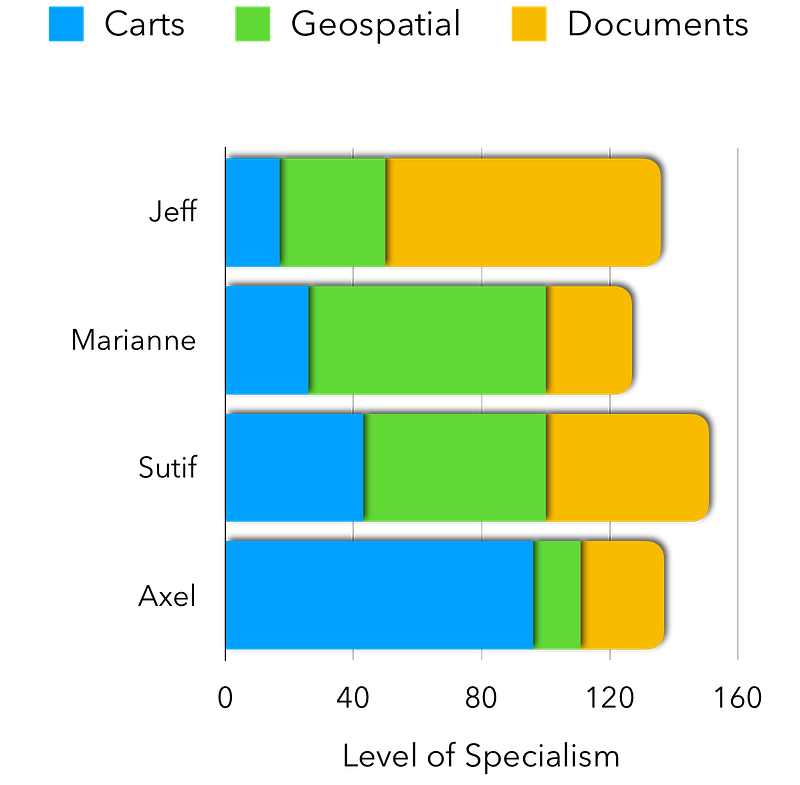

As described in the flow section (Work Item Delivery Flow), the chosen approach has both positive and negative consequences. The mind-map shown below displays the main working qualities to consider.

KNOWLEDGE IS THE BIGGEST CONSTRAINT

The biggest constraint for businesses in building software is not the technology, nor the development or testing activities. It is the percolation of contextual information (knowledge) down to all parties - the Shared Context.

I realise that any form of discussion affecting how others work is emotive; however, I ask that you consider all three of the following (important) perspectives:

- Individual. What’s best for individuals?

- Team. What’s best for the team?

- Business. What’s best for the business?

Let’s visit them.

INDEPENDENT (INDY)

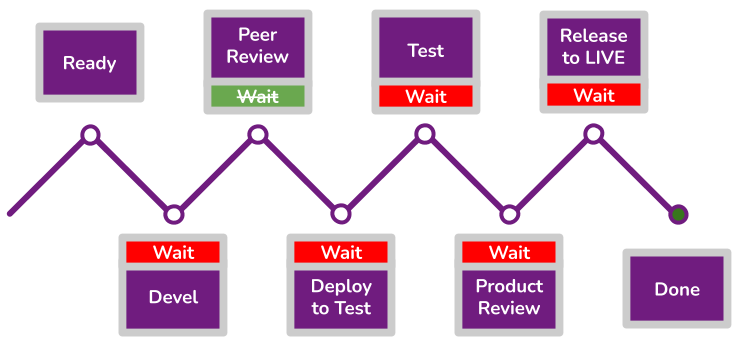

Independent (Indy) development - particularly if you’re remote - can be both extremely gratifying, and a place of terror. It’s the oldest and most established of the three approaches. An engineer builds a new software feature, introduces functional tests (e.g. unit), then marks it ready for peer (tech) review. Another individual picks up the ticket and verifies it, then passes it on to another individual to test it. Once the tester finishes, they mark the ticket as ready for product review. The product representative then verifies it meets product expectations and marks it as ready for release to LIVE. Finally, another individual then deploys it to LIVE where users can use it.

This approach is full of fits and starts and hand-overs as we wait for the next (able) constituent to be free to progress the ticket. Whilst not immediately obvious, each “doing” stage is preceded by a “wait” stage; see below.

Indy development can work very well (it has, after all, lasted the test of time). Unit-Level Productivity can be very good, assuming that: (a) the Shared Context that travels with it is also understood by all others in the assembly line, and (b) that bugs are not introduced, causing rework (thus affecting release efficiency).

It's useful when:

- There’s a critical problem to resolve, requiring deep thought from an expert, and any interruptions must be avoided. Whilst this does happen, consider the root cause. Is the isolation required because it truly needs an expert, is there unnecessary complexity, or is it because you’ve created a Single Point of Failure? This approach also assumes that there are experts lined up (and immediately available) for every subsequent step once the problem is resolved, otherwise you’ve wasted the efficiencies brought about by the expert.

- Thinking time for complex problems that either shared learning won’t help, or that will benefit the individual by figuring it out themselves. Again, there are cases where something is so complex that it needs an expert to reflect on, without disturbance.

- Your business uses geographically distributed teams that can’t successfully collaborate due to time zone differences.

- The individuals in a team don’t (or won’t) pair. It's still relatively common to find this thinking in a culture. Some business (and technology) leaders consider this to be the most productive approach.

- There's no need to collaborate. Certain types of work - such as single-use solutions, or proof-of-concepts - don’t need collaboration.

- Preparation. In some situations we must prepare work before we can undertake it, and it might be best served using Indy development. I’ve seen this approach used to identify/prepare test data prior to beginning testing.

- Unknown quantities. Dealing with the unknown can be like trying to find your way through a maze without a map. There are many wrong turns before the right way is discovered. Collaboration under these circumstances can be deeply frustrating, so the solution may be best achieved through independent investigation.

INDY IS EVERYWHERE

Indy work isn’t limited to one branch of engineering (such as development). It's also commonly done with reviews, testing, and deployments.

However, there are - to my mind - some serious disadvantages to Indy development.

LOWERS SHARED CONTEXT

A reduction in Shared Context. We’re not just handing over software, but contextual information about the problem and its solution; e.g. why it's a problem, why it was solved a certain way, what it can and can’t do.

The start-stop (relay) nature of Indy doesn’t lend itself as well to information sharing compared to the other techniques, even when employing BDD techniques.

REDUCES RELEASE EFFICIENCY

Release efficiency (or Flow) is often reduced. Whilst the unit level productivity may be impressive (e.g. work costs us the effort of one developer, not multiple), it’s unlikely the release efficiency is, as each work item must repeatedly transition and then wait (four or five times) before reaching its final destination. There’s also the question of context-switching, the late identification of bugs, and the time that developers spend repeatedly sharing (the same) context - first in a peer review, then with a tester, and finally with product representatives and end-users.

Additionally, Flow is dictated by the availability (and skillset) of the next person in the chain. Work items will remain in the release pipeline for longer whilst:

- That person becomes available - they’re probably working on something else.

- Context Switching and realignment takes place.

And last but not least, a reduction in Flow also often leads to slower learning (the opposite of what we want - Learn Fast), and therefore more waste (we’re not building value).

INCREASES SINGLE POINTS OF FAILURE

It may increase Single Points of Failure. Let’s face it, working in this style is a form of siloing (a very very small silo), where we create individual expertise, and we miss opportunities to share context and ideas (Shared Context).

“But surely creating expertise is a good thing?”. Yes! Expertise is great in many cases, but it may also introduce great risk, such as with Silos of Expertise. Humans have a natural tendency towards perceived immediate efficiency (and gratification) - particularly if it relates to our own efficiency - so we sometimes forget there are other important characteristics to consider (like Sustainability and Agility). See Unit-Level Efficiency Bias. We also become biased to whom we associate certain activities with - the “Give it to Sam, he’ll have it done in ten minutes” argument.

“Sam” is indoctrinated into a Silo of Expertise (whether he knows, or likes it), requiring no help (being the expert), and subsequently gets every associated change in that area. We now have - amongst other things - a delivery bottleneck.

“BUT THAT'S WHAT THE PEER REVIEW OFFERS?”

"But that’s what the peer review offers?" Hmmm, let me cut you off at the pass. A peer review in this model may well diminish the likelihood of a Single Point of Failure, but it won’t remove it. Remember that this model promotes independent activities, indicating that peer review is also undertaken in isolation (silo number two). Even if it's more collaborative, context is still lost.

The original author simply cannot offer all of the contextual information around their choices, decision-making, discarded options, impact on other areas. The list goes on. Why? Either because they’ve forgotten it, or they may only choose to divulge what they deem relevant. Communication - which is notoriously lossy - depends upon the efficiency of a flow full of fits and starts.

THROTTLING

As we increase velocity in one stage (e.g. development), we may find work accumulating ahead of bottlenecks in other stages (this is termed inventory in Theory of Constraints terms). It's common to see this problem with teams of (say) three or four developers but only a single tester. The tester must contend with two problems:

- They're supporting the work of many others, who may be producing it much faster than it can be tested.

- They must contend with more Context Switching. This isn’t helped when shared context is missed.

We’re forced to throttle other stages and then reassign those staff to support the bottleneck, both frustrating teams and questioning leadership.

A TEMPTATION TO BATCH

A velocity mismatch (mentioned in the throttling section) between the stages often leads to multiple items sitting in a waiting state.

When someone is given multiple tasks to do simultaneously there’s often a tendency to batch them (assuming they’re in similar areas), rather than work on each independently.

This harks back to the efficiency bias I mentioned earlier (Unit-Level Efficiency Bias) - it’s deemed more efficient for that individual to batch similar items. And maybe it is. Yet this leads to other problems. A set of work-items batched at one stage leads to those same items being batched again at subsequent stages, until they’re finally ready for release, where they’re batched a final time as one risky (mini) big-bang release.

IT MAY LOWER INNOVATION

Innovation tends to occur around interactions with others, less so in isolation (that’s invention). [2] But this model offers fewer opportunities to collaborate (I mean together, simultaneously), stunting opportunities for others to see or improve upon a good idea.

CULTURAL IMPACT

The Indy flow still seems the most prevalent of the three approaches, although things are slowly changing. The problem with its prevalence is it’s habitual selection, without considering the strategic goal (which isn’t necessarily the productivity of a single person).

I’ve seen alternative approaches dismissed (and denigrated), simply because they didn’t sit well with people’s habits, or how they preferred to work (Change Friction, 21+ Days to Change a Habit).

I made the point earlier that unit-level productivity may well be improved with Indy development. But individual efficiency isn’t the same (or to my mind, as important) as team, or business efficiency (Unit Level Efficiency v Business Level Scale). Perception is everything. If individual productivity continues to be promoted - mainly for perceived cost savings - then Indy development will remain dominant.

PAIRING

Two heads are better than one.

The idea here is that rather than working on items independently, we form a pair, and collaborate on a problem together. Note that we’re not talking about any hand-offs between the pair (as you typically get with Indy), but two people sitting together (physically or remotely) and completing a task.

TYPICAL ROLES

Pairing typically occurs in either a developer/developer, or a developer/tester form.

Whilst Indy development requires the next person in the chain to be immediately available directly before a work item is handed over (at least for an efficient flow), pairing requires those parties to be immediately available at inception, and for the duration of the pairing. Once begun, those parties should remove any other noise not linked to this goal, else they squander the benefits of pairing (and risk alienating the other party).

FORMS OF PAIRING

Pairing comes in various styles:

The pairing style may influence the outcome and enjoyment.

- Driver / Navigator. In this model the driver and navigator play a different role. The driver remains tactical, solving the here-and-now problems, intentionally not looking at the big picture, and regularly communicating what they are doing. The navigator is strategic, observing what the driver is doing, giving appropriate direction, and watching out for obstacles.

- Strong Style. Like Driver/Navigator, we have a driver and a navigator. However, in this case the driver is doing exactly what the navigator says, and the navigator works in imperative mode (“do this, now do that, and now this”). It's particularly useful if the driver is inexperienced. Context is widened through the act of doing (inculcation).

- Tour Guide. In this model the driver (guide) is an expert and is imparting information to the navigator(s). There’s no rotation as there is in some other styles. The navigator is mainly passive, but may ask questions. This style is useful if we wish to broaden Shared Context to others (e.g. new staff) who are unfamiliar with it.

- Ping Pong. Follows the Red/Green/Refactor TDD practice of writing the test first, and quickly following it up with an implementation. For instance: (a) developer A writes a (failing) test without an implementation, (b) developer B then writes the implementation for that test to make it pass, (c) the code is refactored. The whole process then repeats, this time with developer B writing the failing test.

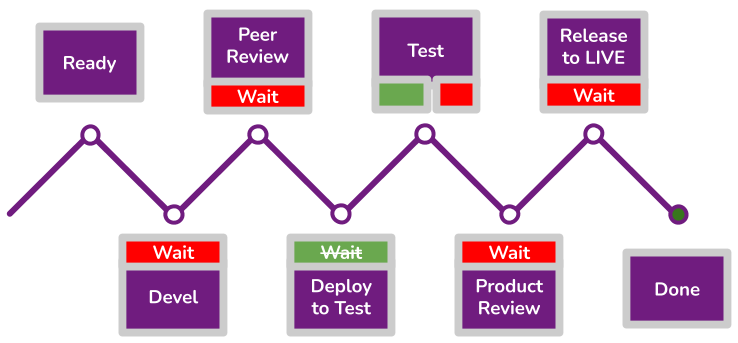

It's harder to visualise the work-item flow for Pairing than for that of Indy, simply because the pairing flow depends upon who (experience, and role type) is in the pair, and the strength of the collaboration. I’ve provided an example scenario of how a Developer/Developer pairing might look below.

Note how we may be able to avoid an explicit jump (the wait and subsequent Peer Review) by having two developers pairing - the assumption being that one of the pair is a viable reviewer (you shouldn’t review your own code). Of course a peer review still occurs, but it's done implicitly as part of the pairing, in real time as the code is being developed, not an explicit “air-gapped” stage that forces a wait (which we want to avoid). This is highly advantageous as improvements occur in real time.

I’ve also provided an example scenario of how a Developer/Tester pairing might look below.

Firstly, we get to introduce (testing) quality earlier in our practices (Shift Left), enhancing automation and promoting Fast Feedback. We’re also widening our Shared Context past development staff, and further reducing the potential for Single Points of Failure. Now, whilst we can’t avoid an explicit peer review stage (we need a second pair of eyes), we know that the tester is comfortable with the functionality (tested locally), so will be happy for it to be deployed once it passes code review. Finally, whilst we cannot extirpate the explicit testing stage - we must consider environmental differences, integration testing etc - it should have been significantly shortened (else the use of the tester had limited effect).

Pairing is useful when we:

- (Generally) Place a greater onus on delivery speed than unit-level productivity.

- Want to broaden Shared Context. We’re sharing more information across a wider range of stakeholders.

- Want to reduce the Single Points of Failure which can hamper a business.

- Want to increase innovation around a specific feature (Innovation). Innovation occurs through interactions.

- Want to increase the confidence, morale, or camaraderie of an individual or group.

- Want to build Trust. People can build relationships when they are given the time and opportunity to share experiences. And as trust increases we find more opportunities for efficiency (less micromanagement), and innovation (see earlier point).

- Have a highly complex problem that is difficult (or unfair) for one person to solve. This falls under the “two heads are better than one” mantra.

- Want to increase quality. We might pair if we know a particular domain is of questionable quality, or if the feature is of vital importance to the business. It's commonly held that collaborative practices produce fewer bugs (than Indy development), and thus less rework.

- Know that the business will need to scale up in that area shortly.

- Want to lower Work-in-Progress (WIP).

- Want to disincentivize Gold Plating. It's easier to inject unnecessary quality into a feature when working in isolation than when working collaboratively towards a shared goal.

However, Pairing also has some disadvantages/difficulties to overcome:

- The culture can’t (or won’t) support it. If a business bases their decisions solely on developer costs (there are others), they may conclude that either pairing equates to double the investment, or that they’ll only be able to deliver half of the features. Whilst I recognise this view, I think it a false economy, heavily influenced by only measuring a single parameter.

- There are relationship issues within the team that pairing won’t alleviate (maybe you’ve tried). There’s still plenty of individuals who prefer to work alone.

- Aggregated Availability. Indy development only needs one person available per stage, whilst pairing requires dual availability at point of inception. The pairing duration (length of time) can also create availability contention.

- An insufficient focus on shared goals. It's more difficult to get two people together if their goals (or focus) differ; e.g. “Sorry Poe, I’ve got this two-hour meeting this afternoon that I can’t get out of. Can you wait till I’m finished?” You might start by asking why there are competing goals?

- The pairing dynamic, such as clashes of personality or approach, may affect the quality of the outcome.

- Frustration. Any form of collaboration (including pairing) can create frustration. For instance, if one party feels that they must explain every minutiae, they feel their work is being assessed (not the purpose of pairing), or if there’s a disproportionate partitioning of effort, thinking, or mismatched work ethics within the pair.

- Remote tooling. The COVID crisis has attenuated the need for remote pairing. Whilst there are certainly good remote pairing tools on the market, I still regularly hear pushback to remote pairing based on this.

- Scared context. Whilst I hope this doesn’t happen often, you may find some people trying to protect their jobs by intentionally not sharing information, thus creating a specialism and becoming a Single Point of Failure.

- Cognitive overload or tiredness. Pairing can be intense, requiring periods of sustained focus driven by two people’s expectations. It's easy to get lost in the moment and forget to take a break.

- Dealing with an unknown quantity. I’ve seen this a few times, where a pair/group was capsized by a problem that no-one had a (immediate) solution to. It’s best in these cases to disband and reform once the path becomes clear.

Note that most of the disadvantages/challenges are based upon: cultural issues (“I don’t want to work with them”, or “why must I share, I’m the expert!”), unknowns, or leadership challenges (such as making time available for people to pair, or ensuring the team is working on the same goal)?

MOBBING

Mobbing is the formation of a group (mob) of people all working towards a common goal. It’s different to pairing in both the number (and skills) of participants, and in the manner in which work is undertaken.

Bringing together a mob of individuals, of diverse skill sets and knowledge, allows us to use the power of many brains to solve a single problem. Developers, testers, operations, DevOps, Security, business analysts, and product representatives all get the opportunity to be a part of the mob.

Of course bringing together a diverse group of people and enabling them to successfully collaborate requires some structure and rules. A mob is typically structured around the driver/navigator style - however, the navigator in this case may be everyone other than the driver. Regular rotations are used to promote engagement and collaboration.

STRICTER STYLE

In the stricter style, only the driver and a single navigator are encouraged to directly interact, whilst the other participants are asked to remain silent (listening mode) so as not to disturb flow, or to steal learning. It is - however - common for those other participants to engage (through the navigator) if they think they can add value; it's the navigator’s choice as to whether to accept their help.

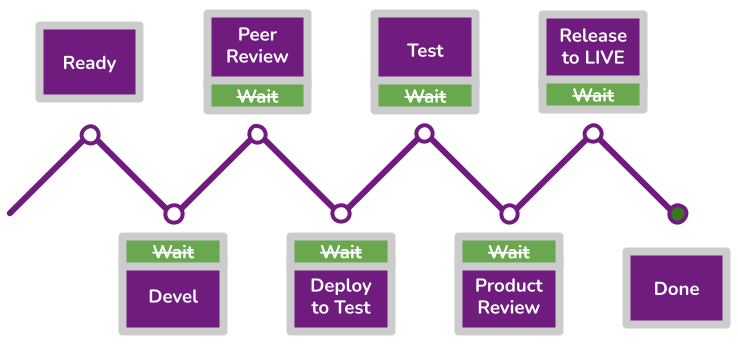

So, why mob? I’ve indicated a potential flow when all stakeholders are fully engaged in delivering a work item through a mob.

Note how much ground it covers. There’s little - if any - waiting. In fact, it’s quite possible to get all the way into production without any waits! Think of the possibilities. An important feature can be started, implemented, and released to users in (say) a few days, with little pause, enabling us to gain an early insight into how successful it is (all features are just a form of betting).

KNOWLEDGE IS THE CONSTRAINT

I made the point earlier that knowledge (Shared Context) is often the biggest constraint to a business, hampering business agility and scalability. Mobbing can help to resolve this.

Mobbing has many of the same benefits (and drawbacks) as pairing, albeit more extreme. Mobbing is useful for:

- Broadening Shared Context. Everyone gets the context (whether they need it, or want it), further reducing the potential for Single Points of Failure, and enhancing business Agility.

- Improving Delivery Flow. Whilst all three styles execute the same types of activities (e.g. peer review), that doesn’t mean they all need to be done sequentially, or incur a wait penalty. Mobbing takes pairing to the next logical level. Why pause after peer review (or testing) when the group has all the input and authority needed to release software to production? Mobbing helps to remove many of the impediments that slow down the release of change.

- Improving Group Flow [3]. I don’t mean delivery flow, but the flow that can be attained by a team working in harmony.

- Innovation occurs through interactions. The greater the number of interactions, the greater the potential for innovation.

- Significantly lowering Work-in-Progress (WIP). Everyone works on the same work item, for the same goal. There's no Context Switching as there’s nothing to switch to.

- Simplifying the management of software production. Managing a single team, on a single work item, is much easier than trying to manage many teams with many work items (try it). Mobbing minimises the possibility of mixed messaging, aligning everyone around one central theme.

- Fast Feedback and Shift Left. We can inject quality (at the appropriate level) into our practices much earlier.

However, Mobbing has some of the following challenges:

- Bringing many people together - of diverse experiences - can be extremely difficult. It’s difficult with pairing, but even more so with mobbing. Even if people work on the same team-level goal, they’re often still needed to support other strategic goals across the business.

- Team size. A mob of ten is likely to face different challenges (communication) than a smaller mob. If this is the case, it might be worth considering team structures. Are they too large? See Two-Pizza Teams. [4]

- Getting value from all parties. For instance, we can’t expect that all stakeholders are willing to write code, or can offer domain expertise. Remember though that value might be realised at a future date due to the broadening of shared context.

- It may not be appropriate for solving simple problems, or ones with a limited lifespan. For instance, engaging three developers, two testers, and a product representative to solve a simple API change is probably overkill and may lead to frustration or resentment. Whilst we should always consider all important working characteristics, we shouldn’t ignore unit-level productivity.

- A strong preference for Indy development. There’s little point in forcing mobbing practices on people who don’t want to use them. I’ve seen a lot of pushback on forced mobbing that isn’t worth the cultural impact.

- Remaining focused for extended periods is difficult - probably more so than with pairing - and requires regular breaks.

- Frustration may be much higher than with pairing (but so too can the ecstasy), simply because people are waiting longer for an opportunity to code, and don’t always consider what they’re providing is of value (it is of value, but just in a different way).

- Unit-level bias. The overarching business may be too preoccupied with unit-level productivity to consider other important working characteristics, such as delivery flow, or shared context.

A PRODUCTIVITY KILLER?

I sometimes hear the following argument about Mobbing: “Mobbing is a productivity killer.”

And I agree, in a sense; but they’re missing the point. Mobbing is not catering to individual (unit level) productivity. Whilst a proportion of the mob isn’t actively building code, there is something happening. Skills are being learned and honed. Relationships are being fostered. Communication, alignment, and a Shared Context is being built. Innovation is being cultivated. Business Agility and scalability (in the non-technical sense) is improved, and the scheduling of work is simplified.

SUMMARY

“Ok, so which approach should I use?” Well, the short answer is all of them. Each approach is useful in different scenarios.

“But which one is better?” Firstly, can you define “better”? It’s meaning can be very subjective, and heavily reliant upon individual perception (and bias). It’s also - I suspect - the reason why these techniques are so hotly contested.

I quoted this earlier: "A good falconer releases only as many birds as are needed for the chase." - Baltasar Gracián. [1]