Performance

PERFORMANCE

| TTM | ROI | Sellability | Agility | Reputation |

The ability to respond to a request within an acceptable reference of time.

Performance is a measure of the length of time from initiating an action, to receiving a correlated response. For instance, if the initiator is an end-user submitting a web form, the performance they receive is the duration that the user waits for the system to respond back to them in some meaningful way.

PERFORMANCE & LATENCY

I sometimes use the terms performance, latency, and response time interchangeably here, when they are in fact distinct concepts. My intent is not to add confusion, but simply to reduce some of (sometimes perplexing) vocabulary, which is laced with technical terms such as: latency, response time, page load time, and time-to-first-byte (TTFB). Some of you will know that these concepts aren't entirely interchangeable - but it's good enough for my purposes. Find a good article online if you'd like to understand these concepts better.

The two concepts I'll stick with here are:

- Performance - a more generic term used to represent a system quality (or characteristic if you like).

- Latency - a specific concept used to measure performance. In earnestness, when I hear most people talk about measuring performance, they don't talk about response time or latency, but simply use the term latency to indicate the overall time (i.e. response time). It's ambiguous, but I think it's right for my audience, and the definition I'll use here.

Firstly, let's discuss why performance is important. Fundamentally, performance is a metric of wait time - i.e. the duration a requester must wait for a response. This is important for two reasons:

- It is a critical aspect for some roles or industries in order to succeed, or to remain competitive.

- It is a decent predictor of how your users (or prospective customers) perceive your system, and therefore your business (reputation).

Let's start with the first point. Imagine for a moment that you worked in one of the following roles: motor racing driver, airline pilot, air traffic control, nuclear facility manager, high-stakes financial trader. Their ability to receive (and contextualise) information in a time-critical fashion is an essential aspect for them to perform well. A failure in these circumstances could have catastrophic effects, including loss of life, or significant financial or economic hardship.

A thousandth of a second can be the difference between winning and losing in motor sport. Whilst tardy information (responses) may cause a pilot, air traffic controller, or nuclear facility manager to make the wrong decision. A delay of a fraction of a second in high-speed trading could give your competitors an unfair advantage over you, resulting in millions of dollars of lost revenue. In Alexandre Dumas' novel The Count of Monte Cristo, Baron Danglers amasses a small fortune through insider trading, by receiving important information, before others. The Count uses the telegraph (and some social engineering) to publish false information and therefore impoverish Danglers [1]).

CO-LOCATION

High-speed traders pay top dollar to have their servers co-located within an exchange to gain the benefits of low latency, and therefore the financial rewards of high-speed trading [2]. This is known as The Principle of Locality.

TITANIC

There are many (often conflicting) aspects to the Titanic story. Some we'll never fully know. However, it's widely accepted that a key reason for the Titanic's impact with an iceberg, and its subsequent foundering and grave loss of life, was that the lookouts in the crow's nest didn't see the iceberg until very late (they should have had access to binoculars, but these had been locked away when another crew member left the ship). By the time the lookouts saw it, had rang the bell (three times for “iceberg directly ahead”) and then reported it to the crew, who then needed to decide on their course of action, it was already too late. Their decision to turn was too little too late, due to the late delivery of crucial information.

My point then is that failing to deliver information, in a time-critical situation, can be catastrophic.

As for the second point, performance is a good indicator (or predictor) of how users perceive your system, and therefore your business. Systems that respond quickly tend to be well received, whilst ones with glacial responses receive criticism. A number of user research studies have been conducted on the relationship between user wait time and user engagement [3]. The metrics are interesting. For instance, this report suggests that: “The probability of bounce increases 32% as page load time goes from 1 second to 3 seconds. (Google, 2017)” [4]. A “bounce” may mean a lost sale (bad), it may also mean a lost sale to a competitor (doubly bad). Performance also plays a role in website rankings, with websites that respond quicker placed higher in certain search engine rankings (and thus seen sooner by users).

Ok, so now that we've discussed why performance is important, let's see how it is measured within software systems. I've visualised it below.

This is an example of a remote interaction - one that involves a communication between two (or more) machines to fulfil a request. At a basic level, it's composed of:

- Transformation time - the time taken to transform information presented to the user (such as a web form), or another system, to something that can be transferred across a network (such as a JSON payload), and back again.

- Transfer (or travel) time - the time it takes for all of the data packets to be transferred (and routed) across a network (typically the internet), and back again.

- Processing time - the time it takes to process the request in some meaningful way. This depends upon the business and transactional context.

COMPOSITE OF ALL

For complex transactions, we may find these same actions are undertaken many times. For instance, if we consider a cart checkout - it might create many distinct sub-transactions, each requiring its own transformation, travel, and processing.

Numerous things can affect performance:

- The sending machine is slow - for instance, this might happen when a labour-intensive process is currently running on it.

- The network between the sender and target machine is slow, or involves many hops.

- The target machine resides in a different geographic region; discussed next.

- The action of transforming the (payload message) contents to and from something that the current machine understands is intensive. For instance, you might get this when sending large documents.

- The action(s) being performed by the target machine (or machine) is labour-intensive or slow. This tends to be the most common cause of poor latency, especially if the actions are involved or multifarious. However, these steps may also be inescapable.

GEOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES

The “global reach” of some businesses creates other challenges. More and more businesses now operate 24x7, serving customers across the globe. In the old days, we might have treated each region as a distinct business unit, with distinct systems and reporting capabilities. But this is rather limiting. For example, if we want an accurate picture of all of our customers, support a global catalogue, or market a global offer, then we have a challenge. It's a problem similar to the one faced by businesses supporting a single tenancy model with multiple customers (System Tenancy).

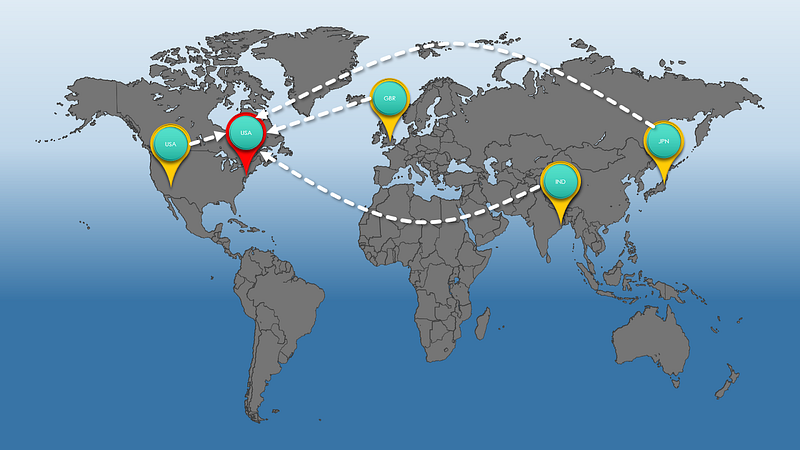

One solution is to deploy all of our services into a specific geographic region and serve all of our customers from there. You can see this below, with the red pin representing the servers, and the blue pins, the customers.

Unfortunately, this is a rather simplistic view. You certainly gain in terms of consistency and (some) simplicity - e.g. you need only manage a single product or service (Uniformity), and reporting becomes easier since all events originate from a single source. But performance now becomes a problem. As represented above, let's assume our business uses a cloud vendor's services on the US east coast (since much of our custom is in the US). This ensures that most of our US customers get low latency requests, and thus a good user experience. However, we also have strong user bases in the UK, India and Japan. For UK customers, whilst the latency is worse than the US, it's still acceptable. Not so for our Indian and Japanese customers though. The round trip to the US, and then back, is too long to be an acceptable user experience. What it tells us is that achieving a consistent latency (and thus experience) for all customers, across all geographic regions, can be quite challenging.

The obvious solution is to bring our customers and the services we offer them closer together. So US customers (and possibly UK customers) can use our services based in the US East coast, Indian customers use data centres in East India, and Japanese customers use those based in Japan. All of our customers now receive excellent performance, but (guess what?), it's now created a different problem. For instance, if we now have multiple regions modifying data sets, how do we get a centralised view across our entire business? What about data synchronisation, or the potential for competing transactions (e.g. two regions modifying the same customer record at the same time)? Which region should we treat as our cardinal data source in order to report from?

TECHNOLOGY DICTATING BUSINESS OPERATION

On another note, we don't (necessarily) want our technical solution to dictate how our business operates (or indeed our culture), else we find the tail wagging the dog (Tail Wagging the Dog).

The CQRS pattern [5] offers one solution, but Cloud vendors are also offering out-of-the-box solutions to this problem.

PERFORMANCE AND SCALABILITY

Whilst performance and Scalability aren't synonymous (Scalability relates to the system's ability to manage variations in throughput, whilst performance relates to the system's ability to respond to a request within an acceptable time frame), they are linked. For instance, we often find that performance is impacted as system use increases, eventually leading to Availability issues.

Performance is one quality I often see a (over) bias towards, particularly against Scalability. Partly, this is because latency is a relatively simple metric to measure (at least at the fundamental level), enabling us to shift-left on it, but it's also a runtime non-functional quality that's immediately obvious to users, and at all times. And finally, there also seems to be some inherent myth that every system needs to be blisteringly fast.

This final premise is untrue. Certainly, there are cases where performance is critical, or it affects user engagement to the point of distraction, but it isn't an encompassing issue across every persona or product. A better set of questions might be to ask yourself whether your users would care (or even notice) if they experienced a 0.25 second increase in lag (for example), and could you leverage that additional leeway to better scale and evolve your systems?

FOR EXAMPLE

It's relatively easy to test latency, such as in this requirement:

“Calls to API x should complete within 2 seconds”.I could spin up a local environment and test this almost immediately, simply by throwing a handful of requests through and measuring how quickly it responds. But it's not an accurate reflection of how software systems are actually used, such as in this requirement:

This is a significantly harder requirement to prove, involving aspects of performance, scalability (throughput specifically), and (even) availability.

“The 99th percentile of all API calls should complete within 2 seconds, with a load of 100,000 active users in the system”.

PILLARS AFFECTED

ROI

If not contained, poorly performing software can lead to significant future rework, thereby affecting your return. Additionally, as it takes longer to complete each transaction in underperforming software, it results in higher operational costs, particularly if costs are measured by transactional duration (e.g. Serverless).

SELLABILITY

I've already suggested that performance is a good indicator (or predictor) for how users perceive your system, and therefore your business. This is equally true for prospective customers in the sales process. Arguably this quality also relates to pride. Ultimately, does the business promoting its poorly performing solution to its customers truly have pride in their offering? If your prospective customers consider your product sluggish, treat it as a blemish on your product's sellability.

REPUTATION

Again, if performance is a good indicator for how users perceive your system, then a poorly performing solution will receive criticism and affect the owning business' reputation.

Interestingly, poorly performing systems can also create Availability and Usability concerns. For instance, a software product averaging thirty seconds per user interaction will quickly lose user interest and traction (who may be quite comfortable venting their frustrations on social media platforms), but also the confidence of the owning business stakeholders (Stakeholder Confidence). All to the detriment of the owning business.

SUMMARY

Performance is important either in any temporal activity that requires a speedy response to be useful or important, or to retain user engagement. However, please beware that this can also lead to a performance over-bias, causing us to make rash (unnecessary) architectural decisions to overcompensate for a performance requirement that doesn't exist.

OVERENGINEERING FOR PERFORMANCE

I once worked on a product where the engineers integrated directly with the domain model, regardless of domain ownership. There was no delineation of domain responsibilities (nor the Principle of Least Privilege [6]), so each domain was allowed to dip into another domain's data model to access its data, or join tables across multiple domains. Performance was one oft-quoted reason for this approach.

Unfortunately, this approach was seriously flawed, and led to serious Evolvability and Scalability impediments. See Domain Pollution.

Without too much effort, we can link performance to the following qualities:

- Scalability - e.g. poor performance means you can process fewer transactions, affecting throughput.

- Availability - e.g. poorly performing systems become unusable and thus are deemed unavailable.

- Useability - e.g. users simply get fed up waiting for their transaction to complete.

- Resilience - e.g. a single failure where everything is co-located (a technique commonly used to create performant solutions) can bring everything down (house of cards), and make it difficult for individual components to continue functioning or be autonomic (e.g. consider the approach taken in Microservices or Containerisation).

FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS

- [1] - https://spectrum.ieee.org/what-the-count-of-monte-cristo-can-teach-us-about-cybersecurity

- [2] - https://theweek.com/articles/493238/wall-streets-secret-advantage-highspeed-trading

- [3] - https://developers.google.com/search/blog/2010/04/using-site-speed-in-web-search-ranking,

- https://www.browserstack.com/guide/importance-of-page-speed-score,

- https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/page-load-time-conversion-rates

- [4] - https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/marketing-strategies/app-and-mobile/page-load-time-statistics/

- [5] - CQRS - https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/architecture/patterns/cqrs

- [6] - The Principle of Least Privilege - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principle_of_least_privilege

- Containerisation

- Cloud

- Domain Pollution

- Microservices

- Serverless

- Single v Multi Tenancy

- Stakeholder Confidence

- Tail Wagging the Dog